1988-1989:Part Two

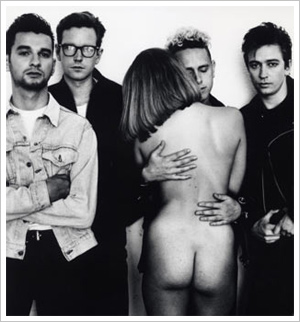

Photo by Anton Corbijn. Reproduced without permission

ALBUM REVIEWS

101 (Live) - released March 13, 1989

"Gone are the days when artists released live LPs purely as a quick and easy way to fulfil contractual obligations. No more are we fed a haphazard collection of songs that sound like they’ve been recorded on your dad’s Fidelity music centre.

Now the capturing of the ‘live experience’ has become as techno obsessed as the studio variety and, as Depeche Mode have proved themselves at the forefront of that environment, so they’ve come up with a double LP celebrating their last US tour that’s as clean as Mary Whitehouse’s diary, but with rather more going on between the lines.

So clean, in fact, that on many of the 17 tracks here, there’s little difference from the original records, with even Dave Gahan’s famed live guttural yobbo yells being mixed down to give added emphasis to his remarkably strong vocals.

Most live albums try too hard to recreate atmosphere at the expense of the quality of the songs. The recent ‘Rank’ from the Smiths being a good example. They sound, quite simply, a bit ropey. ‘101’ avoids this admirably, making full use of modern post production techniques to deliver an energetic, well-recorded – and above all, good and loud – sound, while at the same time producing a quite exceptional ‘Greatest Hits Part II’ collection.

With only ‘Just Can’t Get Enough’ remaining from the Vince Clarke era, later tracks like ‘Behind The Wheel’, ‘ Stripped’, ‘Master And Servant’ and the disturbingly erotic ‘Never Let Me Down Again’ sit like a dark shroud around the group’s traditional fluffy pop framework.

‘101’ is not so much a better than average live album. It sits as a timely reminder of Depeche Mode’s position as one of the few truly subversive pop groups around at the moment." ****

Eleanor Levy

Record Mirror, 11th March, 1989

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

FRENZIED

72,000 sunny Californians go monkey-poo to the pitch-perfect sound of Depeche Mode

"It is really not Depeche Mode’s fault, and certainly no reflection on the quality of a note-perfect performance, that by far the most striking contribution to this live double album is not made by the group at all. As side one’s synthy gothic fanfare is bleeping and pulsing towards its atmospheric conclusion you begin to hear a random selection of high and low frequencies. These are not, as first seems likely, another of DM’s machines warming up, but the more unshapely racket of 72,000 young Americans going absolutely apeshit. And they don’t get any quieter.

They make a frankly bizarre accompaniment to synth-pop so spare, clean-cut and, in a Northern European sort of way, restrained. But in Pasadena, California, the neatly groomed boys from Basildon are evidently regarded as stadium rock giants and for the next 75 minutes we are seldom allowed to forget it. "Good evening Pasadeenaaah," Dave Gahan gamely roars to a crowd which has just tried (unsuccessfully) to clap along to the metronomic beat of Behind The Wheel. "Thangyoooo," he yells above the hysteria which regularly greets the end of everything. "I can’t see yooooo," he bellows during an acapella section of Just Can’t Get Enough. And so it goes on until the very last item of the album, Everything Counts, where he has this frenzied horde happily singing along on their own.

As a general reflection on how oddly things travel – and what odd things American audiences can be – this is all very interesting. But as a recording 101 hardly amounts to an audio gourmet’s delight. Depeche Mode make music to tap your toes to rather than stamp your feet, and the wry ironies of their lyrics are not really designed to be roared at. The suspicion dawns that the joke behind the title of their one American hit People Are People – that people are rather "difficult" – has not been let into the party. And indeed, when Gahan tries to go reflective on the ballad Somebody [Martin sings on this track - BB], Pasadena just carries on noisily making whoopee during all the quiet bits.

There are a few points when the music and its riotous reception meaningly converge: the Chuck Berryish styling of Pleasure Little Treasure, and a big, thumpingly extended rendition of last year’s hit Never Let Me Down Again. But on the whole this is a live album that sends you back to DM’s studio work wondering if you and those 72,000 Californians have been listening to the same records." ***

Robert Sandall

Q, April 1989

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo by unknown photographer. Reproduced without permission.

LOVE IT OR SHOVE IT

"I have to declare an interest here. I’ve been a serious Depressed Toad fan for ages, but even I have to admit that the live sphere is not their forte.

Here they’re static – three men confined to their samplers with only the whirling, tumbling Dave Gahan to afford them any excitement. And this is the problem that dogs their new 101 film (of which this is the soundtrack).

The problem is not the material. Martin Gore’s songs are extraordinary, hugely effective slices of electropop, that blend his deceptive pop sensibility with a strange, often perverse outlook on life. Indeed, Depeche Mode go out of their way to try and build some excitement into the proceedings, filling their music with unusual and elegant sounds and samples, which go some way towards eliminating the essential tedium of the live experience.

Rather it’s the sequence of songs. There’s no feeling of growth, of development, nothing to make "Stripped" (one of Gore’s most eloquent lust songs), which begins side two, more of a peak than "Behind The Wheel" from side one. Nothing that makes "Grabbing Hands" ["Everything Counts"], the final track, a climactic ending to the set. Above all there’s nothing that really gives you the feeling of actually having been there.

It’s something of which Depeche Mode are well aware, and while the line "Though my views may be wrong / They may even be perverted" ("Somebody") may show us where Gore’s mind is, the lyric "You know my weaknesses / I never tried to hide them" ("The Things You Said") seems to be the key here.

Beautifully packaged, with an inclusive booklet of snaps from the event, "101" is above all a fan’s LP, its 17 tracks all available in better condition elsewhere. The film’s genius may have been to take a busload of kids across America on a real rock’n’roll orgy rather than focusing solely on the band. Here there are no such safety nets, no diversions, and what you see (or hear) is what you get.

Depressed Toad – warts and all." ***

Sam King

Sounds, 11th March 1989

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

INTERVIEW

Francesco Adinolfi talks to Martin Gore about the '101' film in the 15th April, 1989 issue of Melody Maker.

BOYS ON FILM

Martin Gore leans back into the soft leather upholstery of the Kensington Hilton hotel and attempts to convince me that Depeche Mode haven’t just committed commercial suicide with "101", the title of both their live album and feature film. Why do a pop band need to make a film? What’s the point of making music movies in 1989, when even U2’s "Rattle And Hum" was a comparative failure?

"Well, I think with us it wasn’t really a serious analysis of our career," he smiles. "And on the other side, this was the right time to do a film. We released a live video in 1984, called "Live In Hamburg", but we felt that it wasn’t finished very well and that it could have been done a lot better. 1984 is a long time ago…

"I think "101" is quite interesting," he adds, "although I’m still very skeptical as to whether it’s gonna work in the cinema. But it will definitely work as a video cassette for fans. Music films have a very limited appeal, especially in cinemas. When you take a film like "Rattle And Hum", you see that it was given a big promotional push and nevertheless it flopped, because music films appeal only to music-conscious people, to those who are into that band."

When was the film originally planned?

"We were planning it around March last year. And we met D. A. Pennebaker just before the American tour started, which was in April. He came on most of the dates in America. He finished filming the concerts in June and then he started to edit. He also recorded a lot of stuff backstage and at the hotels."

Pennebaker is best known for his Sixties documentary of Bob Dylan, "Don’t Look Back", but has usually steered clear of rock since then. Why did you choose him?

"In the beginning we considered using one of the most commonly used film-makers, someone who was contemporary, one around at the moment that most bands use, someone who could decently film our concerts. But then you end up with the standard film that every band gets these days!

"We decided we should do something a bit more interesting, a bit more intellectual and that’s when we had the idea of using D. A. Pennebaker. He hadn’t done anything really musical for quite a long time – he has always been involved in film-making, but in terms of the music industry that’s a new film for him.

Money seems to be a basic theme to the film…

"Yeah, that does come across as being a major element but the show is the basic element," says Gore.

"The film is supposed to be an honest, candid look at a band on the road and what happens backstage. Every night the accountant is backstage talking to the promoters, hassling them about money and money is a big part of the music business, which is very capitalistic."

When was the last time you did a charity gig?

"We are wary of doing big charity concerts because some of the people involved are concerned about the cause, but in a way they’re using the charities for their own ends. If you look at things like the Mandela Concert or even Live Aid you notice that a week after at least half the bands had a single released and it’s not just coincidence, it’s because they know that at the moment everybody is thinking, ‘Oh what a lovely group’. We were asked to do this Armenia Aid in Russia but we said no. I mean, for us it would have been perfect timing because it happened the week our album was released."

Sometimes a live album turns out to be an artistic pause due to lack of creativity. Are Depeche Mode just marking time, waiting for a new rush of inspiration?

"I don’t know if the double album marks the end of a period for us as a band, but it certainly marks the end of an era, the end of a decade. We started in 1980 and this album is coming out in 1989 and our next studio stuff won’t be out until 1990 when we will be moving into the next decade. Maybe we will have a new single out this year, but it’s not sure.

"The album is basically everything that we played live. Before we go on tour we always have a big argument among the band members cos everybody has his favourite songs and we have to sit down and thrash it out and we end up with a list that everybody is sort of happy with but never in full. We recorded the concert at the Pasadena Rose Bowl (Los Angeles), our 101st show of the world tour."

Did you try to achieve an inherent common theme to the songs?

"I think so. There is definitely an inherent quality to the songs that links ‘em all together. But it depends on how far you wanna go. For the first album Vince Clarke wrote most of the material and I didn’t take songwriting very seriously in those days, but with the second album Vince had just left the band and I suddenly had to come up with 10 songs. A lot of the tracks were written when I was very young. So I think that from ‘Construction Time Again’ there is some kind of link between the songs.

"Sometimes it’s very obvious, there are things like references cos I really like references to other songs. In ‘Shake The Disease’ there’s a reference to another song. You know it says, ‘Now I’ve got things to do and I’ve said it before that I know you have too.’ And in another song it said, ‘Now I’ve got things to do and you have too.’ I really like those kind of references."

You’ve been accused of becoming a mere pop band lately. Do you agree that your music has become far too accessible over the years?

"No, not at all. I think when we first started we were more commercial. Our first two albums were really pop and I don’t understand when people say to us now, ‘Why have you become so commercial?’, and a lot of people do.

"After that initial phase, the samplers came along and we got into working to a certain formula. For example, I would write the songs and then we would do a lot of sampling and experiment with sounds, especially on ‘Construction Time Again’ where we used a lot of industrial sounds. We’ve always worked to the same sort of formula, it’s just that we’ve used different noises."

Do you still have ambitions to change your style of song?

"I think it’s now time for us to change our musical approach. Over the last four albums we took our formula to perfection and now we wanna step back and analyse what we’ve done and try to change it. In some ways we like the more minimal things and I think we’ll move back to a more minimalistic approach."

Will that include experimenting with new instruments?

"We’ve always believed in electronics. We came to the public attention with the big electronic boom in the early Eighties and after that we were one of the few electronic bands that carried on with the faith, that believed in it. There was a time in the mid-Eighties when everybody was saying to us, ‘Why are you playing electronic music!’ They wanted us to return to folk, or whatever the latest trend was – the laid back jazz, like Sade, Style Council etc. But we really believed in what we were doing and now we feel like we’ve been justified by the reappearance of electronic music, be it Acid, techno or New Beat. It’s kind of confirmation that what we were doing in the past was artistically right."

Apart from his work with Depeche, Gore has just finished his first solo project – a mini-EP. Six cover versions of songs written in the early Eighties which will be released in May. [This is not true of all the songs on Counterfeit - BB.]

"A lot of people, when they do cover songs, they choose quite famous songs that people already know. But most of the songs I’ve covered, people won’t know, using the same approach to them as with Depeche Mode. Samplers, computers, but it’s just me."

Like the film and the album, Gore’s efforts won’t be what the public expect.

What do Depeche Mode expect from the public?

"I hope they understand us. We try to put some realism into our music – if people see the film, they would see that we are not the serious people that they imagine. There’s a lot of humour in ‘101’ and there aren’t any scenes where you see us sitting down and discussing philosophy.

"We have fun, but we take our music very seriously. We are very realistic and because of that we get accused of being a depressive pop band. I can’t understand that."

Nor do any of his fans.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

ARTICLE

THE UNLIKELY LADS

by Mat Snow

Q, April 1989

_____

The latest stadium-filling attraction in the States is a band that began as a cheaply equipped electronic pop act from Basildon. Today, Depeche Mode are outselling even the "Monster Of Rock" who have ruled America's heartland. And the dollars are piling higher and higher ... "But you're not supposed to talk about that," they remind Mat Snow.

IT is a balmy June evening in the well-heeled Los Angeles neighbourhood of Pasadena, and 72,000 fans congregated in the Rose Bowl are baying for a group who have been so long part of pop’s furniture in their native UK that such adulation is hard to credit. But there it is – Depeche Mode are massive in the state of California, which, if it had sovereign status, would rank as the ninth richest country in the world. And this, the 101st concert in Depeche Mode’s 1988 world tour, capstones their global growth over the last seven years. This crowning achievement, moreover, is to be filmed by none other than D. A. Pennebaker, whose mid-’60s ‘rockumentaries’ Don’t Look Back (with Bob Dylan) and Monterey Pop remain masterpieces of fly-on-the-wall and in-concert footage.

Small wonder then that singer Dave Gahan, normally an unruffled pro before a gig, has never been so nervous in his life. What do you say to 72,000 fans? Backstage, members of the Mode entourage are batting a few ideas back and forth, looking for something to reflect the significance of the event about to take place. Someone comes up with a suggestion, and as greetings go it hardly rivals the welcoming address at a village fete, but it lacks the pithiness Dave is after. "What do you think I am?" he demands, cheeky bravado ill-concealing his apprehension. "Fucking Wordsworth?"

In the end he settles for the succinct "Good evening Pasadena…"

NINE months after that climactic show, Depeche Mode are about to give birth to those by now familiar rock industry twins, the live double album and the movie, both titled 101. A concert version of their 1983 hit single Everything Counts blazes a trail for both projects [The live version of Everything Counts was released as a single on February 13, 1989 to promote the live 101 LP - BB] and neatly encapsulates a theme they have in common, one that seldom is publicly aired by pop groups – the fact that they have made "tons of money", in the gleeful words of their merchandising man at the Rose Bowl as he counts wads and wads of the stuff taken by the T-shirt stalls. A ballpark figure? One million dollars minimum in T-shirt sales alone from just that single show.

"It was a dig at America, the way money corrupts," is Dave Gahan’s analysis today. It’s an argument perhaps polished to a high gleam over the last three days. For Depeche Mode have been flying in, and entertaining at their own considerable expense, pop journalists from all over the world for some marathon PR to launch 101 in all its manifestations. I’m the token representative of the UK, a country of greater sentimental than commercial value to the Depeche Mode of 1989.

"When you tour America, suddenly things like merchandising are far more important than ticket sales," Dave continues, hoarse from the interview rounds. "Merchandise finances tours. People talk about million dollar deals with merchandisers. Before you know it, you may as well be running a chain of T-shirt shops. To tour in America you need to sell T-shirts.

"We like the idea of being quite open about these things, and we hope that people take it the right way. It’s something that’s always taboo with bands, though everybody knows that bands make lots of money, sometimes far too much for what they do. But you must never talk about that because it detaches you from your audience who are supposed to be on the same level as you."

This won’t be the first time Depeche Mode have played fast and loose with their audience, though perversity for its own sake has never been part of the gameplan. We first met them back in 1981, four lads from Basildon, Essex, who sang catchy, danceable ditties which made use of the newly affordable and accessible synthesizer technology that had been pioneered in the charts the previous year by Soft Cell and Human League. Depeche Mode had scored by joining forces with another innovator of what became excruciatingly termed "synthi-pop" – Daniel Miller, a behind-the-scenes boffin who made cult hit records in the guise of The Silicon Teens and The Normal (whose Warm Leatherette was successfully covered by Grace Jones). Daniel Miller’s Mute Records was founded with the purpose of providing a like-minded record company for enthusiasts of the new technology, and his offer to the budding Mode to put out one single, with the possibility of more if it went well, prevailed over the lucrative bids waved in their faces by the majors. Back then Depeche Mode felt they were too young to make a three-album commitment; besides, only Daniel struck the band as entirely honest.

In 1981-2 Depeche Mode could align themselves with Beckenham’s Haircut 100: wholesome, user-friendly boys-next-door, chirpy rather than handsome, guaranteed free of rock posturing and student mystique. The vanguard, in short, of pop’s New Era. It didn’t last. Haircut 100 split and the individuals couldn’t maintain their impetus. By contrast, when principal composer Vince Clarke quit Depeche to form Yazoo with Alison Moyet, Martin Gore stepped into the songwriting gap and immediately took the band into a stranger, more unsettling direction – eastwards, to Europe.

Not only had Dusseldorf’s Kraftwerk long influenced the band, but a new generation of ‘industrial’ groups was coming to the fore, headed by West Berlin’s Einsturzende Neubauten, whose calculated musical dissonance and fetishist image fired Martin Gore’s imagination. The Basildon boys grinning on Saturday Superstore began putting out records called things like Shake The Disease, Master And Servant, Strangelove, Blasphemous Rumours, Stripped and Black Celebration. The world, starting with West Germany, pricked up its ears.

Britain, on the other hand, couldn’t quite handle the transformation. Whereas New Order, operating in similar territory, are treated with awed fascination, Depeche Mode are regarded as something of a joke – a reflection, perhaps, of the fact that New Order’s image has been shaped by the serious rock music press while Mode first beamed forth from the cover of Smash Hits.

"The problem with this country is that we’ve always been underrated artistically," Dave moans. "Earlier on in our career we felt we had to be in everything, the more the better. We were very naïve and because of that we were taken totally the wrong way. We’ve always been very honest. The British press have found it hard to understand Depeche Mode, though I don’t think we’re hard to understand at all. We’ve always had to justify ourselves to the press in Britain and that really offends us; that’s why we’ve avoided talking to them in the last few years. We don’t feel we really have anything to say when the line of questioning is, Why do you exist? That’s another reason to make this film; we wanted to be portrayed as we really were, and if we’re still considered dickheads, then fair enough."

THE "dickhead" problem peaked with Martin Gore’s move to Berlin, where he had a German girlfriend. The image from this period of the goofily cherubic Gore rubbing leather miniskirts with the Cold War capital’s demi-monde became a rock press standing joke.

"I lived there for two years, went out to some clubs and knew a few people, but didn’t take it very seriously at all," Martin smiles, "though it might have had some subconscious influence. The Berlin scene is a bit of a myth – the idea that it’s full of weirdos and junkies, though there are quite a lot. The clubs are quite good but not as shocking and different as people imagine.

"Looking back," he continues, "I’m not very happy about some of the clothes I’ve worn. Every interview we do the skirt is mentioned. I actually think it’s quite funny, though I didn’t look at it deeply. I regret that so much attention was paid to it and that even now there are still people who think I go round dressed like a tranny. I haven’t done it for four years!"

Dave, meanwhile, develops the theme of inadequate recognition in the UK of Depeche Mode’s talents so acclaimed abroad, with the inexplicable exceptions of Australia and Holland.

"This is your home and obviously you want to be taken seriously, and it does hurt when you see things being written about you which are totally wrong; because you’re a pop band you’re not serious. The shame is that there are so many terrible pop bands that are successful commercially and they give pop a bad name. The Beatles, the Stones, some of the greatest bands in the world were pop bands, but it’s become a dirty word over the years now that the image is more important than the music. Martin can’t even read the music papers any more because he finds it so disgusting. The bands, record companies and press are all playing games.

"In the early days we were part of the pretty face scene – though totally unaware of it, I’d like to point out. But our fans have grown up with us and we have a pretty wide-ranging audience. For instance, the average age of our fan club is 20, and to me that seems pretty weird. In America, bands like New Order, Depeche Mode, The Cure, The Banshees, The Smiths and The Bunnymen are grouped in the same category, whereas in Britain they would have totally different audiences. People don’t really know, but perhaps that’s because we’re not on a major label. You read things all the time about U2, and that’s all career-building stuff; they’re now perceived as being the biggest band in the world – because that’s what everyone says."

Dave takes this opportunity to set me right on his own band’s global status.

"For years there used to be a really heavy focus on how big we were in Germany. I used to get it from the milkman, taxi drivers – You’re big in Germany!" he chuckles. "In Russia, apparently, we’ve been voted the second band people would most like to see and buy their records. We’ve heard of people there cutting up tapes and making their own records out of Depeche Mode records – and that goes on all over the world and it’s very flattering. It goes on too in Chicago and Detroit – we’ve met people heavily influenced by Depeche Mode, Kraftwerk and DAF, and new bands like Nitzer Ebb. I don’t think there’ve been many occasions in pop when black music has been influenced by white, and that’s something we’re very flattered by but don’t quite understand, because our music is as white as it comes, very European and not made for dancing."

A transatlantic telephone call to house producer Todd Terry confirms this. Attached to New York’s Sleeping Bag records, the studio whizz behind Black Riot, Royal House (whose Can You Part? is the prototype acid house track) and his own Todd Terry Project namechecks Mode’s Black Celebration album as an influence, and would like to pay tribute by remixing a couple of Mode favourites, "make them more housy; I’d add a harder beat but they have their own sound." In Detroit, meanwhile, Derrick May, leading developer of the sparser house derivative called techno, likewise enthuses about Mode’s clean, European sound. When Depeche Mode paid a visit to the Motor City’s cutting-edge techno club, the Music Institute, they were bemused to be treated as godfathers.

FOR an assessment of Depeche Mode’s more mainstream American following, I turn to Denis McNamara, a producer on station WDRE based in Long Island, New York. WDRE has supported Depeche Mode from the beginning, to the point that they are now one of the top five bands in the area. When the station announced Depeche Mode’s concerts last year, 40,000 tickets sold that first Saturday afternoon, and the band’s freely interpreted B-side version of Bobby Troup’s Route 66 topped the listener’s poll last year. Broadcasting to an average audience of 350,000 people, WDRE’s other mainstays include The Cure, New Order – and now their weaning their listeners on to The Wonder Stuff and The House Of Love.

The importance of medium-sized, Anglophile radio stations such as WDRE in the rise of Depeche Mode cannot be overstated. These champions of what in America is still called new wave music service those kids who consider themselves smarter than the mainstream Bon Jovi fan, and provide a potential stepping stone for bands from culthood to mass breakthrough, U2 being a shining example. Less stratospheric levels can still be lucrative; Depeche Mode, for example, are doing very well thank you on American sales hovering between gold and platinum – that’s not quite the million mark per album. Who are these fans?

"They’re a mixture," says Denis McNamara. "There’s the dance fan, the young female fan who is probably now an Erasure fan also. Depeche Mode fans will be anxiously awaiting the new Cure album, and will have bought Rattle And Hum, but it won’t be their favourite U2 album. They’re not just teen-based; though more female than male, they have a tremendous support among young people between 18 and 28. Part of that came from the spectacular success in the dance clubs of Just Can’t Get Enough, so they’re people who’ve grown up with the band. Then there are the kids who dress in black and also like Einsturzende Neubauten and Nitzer Ebb, the industrial bands. And a lot of our station’s listeners are young urban professionals. You’ll find stockbrokers standing next to a Siouxsie lookalike at a Depeche Mode show."

It is precisely this sort of incongruity which is Depeche Mode’s selling point in America, according to Martin Gore and Andrew Fletcher (known to all as ‘Fletch’).

"The European-ness of us is part of the appeal to the Americans," says Martin Gore. "We’d blow things if we tried to sound American. You can incorporate that into a modern form of music without sounding too regressive."

This is Depeche Mode’s American constituency; the largely urban rock fans who do not buy into the unmistakably American roots sound typified by Bruce Springsteen. To these Americans, Basildon and Berlin are as fascinatingly exotic as New Jersey and Cleveland are to generations of European rock fans. One can attribute the success of Depeche Mode and other British rock bands of their ilk to a reaction against the mainstream dominance of such acts as Bruce Springsteen and Bon Jovi since the Born In The USA phenomenon.

"In the early days in America there was a lot of pressure on Depeche to use a real guitar or drummer, because otherwise they’ll never get out of the clubs," comments Daniel Miller.

"When we first started out until about 1984, we’d go to America and there’d be this really rock attitude," confirms Martin Gore, "while here in Britain they’d accept us because of the electronic boom of the early ’80s. Then suddenly it all turned around."

"The Monsters Of Rock tour featuring Van Halen, Guns N’ Roses, Kingdom Come and Scorpions, four what they call ‘platinum bands’, was doing no business and at the same time we were attracting all the audiences," says Fletch. "These sort of bands tour America every year just creaming in the money, and people have just had enough of it."

REGULARLY touring the States so as to reach out of the clubs where their US record company had narrow-mindedly pigeonholed them, Depeche Mode played to no fewer than 443,012 Americans in 1988.

"People take music in the States a lot more seriously than here," Fletch develops the argument. "Because it’s such an industry, there is also an anti-Top 40 feeling. When we meet people backstage, the thing they ram through to us is, Don’t go Top 40. But if the radio starts playing it and it goes Top 40, what can you do?"

Depeche Mode’s one US Top 40 hit, People Are People, did not, however, alienate their hardcore fans.

"After that the single Master And Servant was totally unacceptable to American radio because of the lyrics, and then Stripped from Black Celebration was also unacceptable." Fletch continues. "So after the success of Some Great Reward we had a slight dip, though we held our fan base, despite no radio play."

Stretching hands, as it were, across America, Depeche Mode are California’s leading "Pretty In Pink" band, as Pet Shop Boy Neil Tennant vividly put it last year.

"Since 1981 KROQ has played them and they’ve now got a huge following here in Southern California. Since Just Can’t Get Enough they’ve gone up and up in popularity," reckons Richard Blade, an ex-patriate English jock at KROQ in Burbank, Los Angeles, which boasts an audience of 1.3 million, averaging 115,000 listeners at any one 15-minute stretch.

"Their breakthrough was in ’84 when they played the Palladium," he continues, "and they did a great show and got such good word-of-mouth that when they came back they sold out two nights at the Forum with a capacity of 17,000, which Duran couldn’t sell out. So six months later we suggested we put them in the Rose Bowl with a 72,000 capacity."

How did they know the band would be so popular?

"Listener response. One out of every three requests we get is for Depeche Mode. We play them round the clock, both new ones and oldies."

KROQ’s current playlist also features The Pogues, Elvis Costello, New Order, U2 – and a new German band called Camouflage. "They’re pretty hot," Richard tells me; "they sound exactly like Depeche Mode." In addition, South California boasts a Mode clone band called Red Flag, formed by two former Liverpudlians. Will the originals, I wonder, crack the wide-open spaces of America’s Midwest, the bread-basket of super-league success?

"Duran Duran did it in ’84 and Depeche Mode have as big a following now as Duran did then. But I don’t know what Depeche have to do to crack the Midwest. MTV used to help, but it’s passé now. I don’t know how the lyrics of Blasphemous Rumours will go down in Kansas. But unlike U2, so far there’s no backlash."

DEPECHE Mode have arrived at the brink of international household-name success without the usual army of managers, advisers and image-makers. Their relationship with Mute and "Uncle" Daniel Miller, for example, is enshrined in a single piece of paper.

"About two years ago we did sign a very small agreement with Daniel because it was pointed out to us, what would happen if Daniel died? He was very overweight at the time, and if he died we wouldn’t be paid a penny," laughs Martin Gore. "So there’s a sheet of paper which says we’re to be paid on a 50-50 basis. In England we pay 50 per cent of all our costs and get 50 per cent of all our profits. In Europe we get 75 per cent of our profits through licensing deals."

Mute’s slice of that action has allowed Daniel Miller to spread his support for the technically innovative and independent-minded, ranging from Erasure and Nick Cave to the semi-autonomous labels Blast First (Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr) and Rhythm King (Bomb The Bass, S’Xpress). While Depeche Mode, for example, try to control their public image far more than in those early careless days, they do so by restricting access. But once they select someone to mediate between themselves and the public, those chosen get a free hand. Avant-garde dub producer Adrian Sherwood, for instance, can sculpt Mode tracks as he likes for his special mixes; and D. A. Pennebaker’s whole modus operandi is unrestricted access and unexpurgated results. "They’re not technicians, they’re artists," says Daniel Miller. "We employ people whose artistic judgement we accept 100 per cent and so we allow them to do what we want."

The only rule, as far as videos are concerned, is that they must be showable on TV. So no swearing, and guns are out. "There was one period of our videos when every single one had a gun in it," Daniel Miller sighs. "They’re dodgy." [I think Miller is talking about Mute acts generally, not Depeche - BB] Most recent promo videos have been shot by photographer Anton Corbijn, famed for his powerful monochrome portraits in New Musical Express in the early ’80s and, more recently, for the last three U2 album sleeves – "I knew Anton but I never thought he’d do a promo for us – he’s far too cred!" laughs Miller. He is also responsible for the cover art of the 101 record, depicting Depeche Mode T-shirts by the bushel, the first time the group have been represented even obliquely on their albums. "It totally sums up a big band in the ’80s," says Anton. "I got to know them and started liking them as people, and realised that my vision of them as a teenybop band was wrong; they’re very crafty and very down-to-earth. They’re like New Order – they do things their way and don’t care what the trend is. Of all the people I’ve worked with, they’re the bravest."

101 the movie is threaded by a narrative concerning Depeche Mode fans auditioned by WDRE in the New York area who make their way by bus to the West Coast to attend the Rose Bowl show. 101 is partially their story, their journey from naivety to self-sufficiency. "Very much like a band," says Dave, "except they don’t have to do a show.

"The words ‘staging’ and ‘script’ don’t come into Pennebaker’s brain at all," he continues. "He films what’s happening and what’s real. The film is honest. That’s why we approached Donn; we saw what he had done with Dylan and Monterey Pop, and the Kennedy documentary – they’re very factual. Too many bands make totally scripted, clichéd films, as glossy as possible."

APPROACHING a big-name rock band for the first time in 20 years, Donn Pennebaker found that a lot had changed.

"The audience at their concert was very intense," says they 62-year-old film documentarist. "The whole thing was presented in such a marvellously imaginative way, far beyond anything I’d imagined or witnessed at concerts in the ’60s and ’70s when you just saw amplifiers and people in their old clothes. Their show was as spectacular as anything you’ll see on Broadway. I figured that anybody who put this much out for an audience would have something between them, else they wouldn’t have done it. I thought it was worth looking into.

"I liked their independence; they didn’t depend on a heavy overhead," he continues. "The process of making successful popular music is about as subject to corruption as making films, so whenever I see people operating independently I’m always impressed. It didn’t mean you were dealing with heavy intellectual forces, like Bob Dylan and whoever else has that strong hold on people’s imagination, but I think that the way Depeche Mode live their lives and make their music is interesting because so few people do it that way."

Like the famous scene in Don’t Look Back where Bob Dylan’s British agent Tito Burns hustles a deal for his star, in 101 Pennebaker revels in the spectacle of Depeche Mode hitting town and raiding its coffers.

"That’s the kind of drama I grew up on – things like Errol Flynn, that whole American sense of adventure that it’s all there for the taking, the Tono Bungay thing," he explains. I wasn’t trying to indict anybody for making money or make fun of the process because it’s much more complex than anybody imagines. When they decided to go into the Rose Bowl, they stuck their heads out a little, and like any entrepreneur or anybody who hunts for treasure, they take a chance. I applaud if they win; I don’t look on that as the process of a foul capitalist machine. I’m not looking to propose an answer, just showing what I see, which is complex and contradictory. What we’re hoping to do in this film is show a simultaneity of views so that people can see the whole thing and make of it what they will. I’m not suggesting any answers nor any point of view beyond that it kind of works.

"With Monterey, the way we filmed it, it may have looked huge, but there were hardly more than 10,000 people at any one time – small-scale compared to this," Pennebaker continues. "This was like a multi-engined aircraft – once you’d decided to land, you couldn’t change your mind. That was one of the things that intrigued me. But they still did it with a sort of insouciance. Depeche Mode had done most of the work with the music, the choreography, the staging and the lights. We just had to stay awake behind the cameras!"

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photos by Adrian Boot. Reproduced without permission.

NEWS ITEM

GORE BLIMEY!

Depeche Mode ran into trouble during the promotional campaign for their new single "Personal Jesus", with some regional newspapers refusing to accept ads for the record.

Both the Aberdeen Evening News and the Nottingham Evening Post rejected classified ads which simply featured the words "Your Own Personal Jesus" followed by a phone number which, when dialled, played the song, on the grounds that they may cause offence.

In London, the Evening Standard also raised objections due to the religious content, but later relented when representatives of the band pointed out that the paper had already run similar advertisements as part of Billy Graham’s "Life" Campaign.

The new single, the group’s first new recording for two years, is released by Mute on Monday.

It was produced by Depeche Mode and Flood and recorded at Logic Studios in Milan. The B side features "Dangerous" and an acoustic mix of "Personal Jesus". Expect more remixes of the single to be released soon. All tracks were mixed by Flood and Francois Kevorkian, best known for his work with Kraftwerk.

Depeche Mode are currently in Denmark where they are putting the finishing touches to their as yet untitled new album, which should be in the shops early in the new year.

New Musical Express, 26th August, 1989

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

SINGLE REVIEW

PERSONAL JESUS - released August 29, 1989

Stuart Maconie reviews the week's single releases in the New Musical Express (16 September, 1989) with help from Miles and Martin from The Wonder Stuff

A hit even as we speak, but in the frantic rush to lionise surly adolescents in black jeans and people with their caps on back to front, we seemed to have overlooked the latest release by the most subversive singles band of the decade. Depeche Mode make criminally brilliant pop records about God, death, crazy sex and alienation and as far as I'm concerned they can do no wrong. 'Personal Jesus' sounds like The Glitter Band in the throes of an intense personal crisis. Huge fun. The Stuffies hated it...

Martin: It's great that they don't play all the Radio One rules, that they remain independent and make these weird records, but I can't say I like them. I don't care if I never hear that again. It's just so cold and lifeless. I respect them but it means nothing to me.Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.