Supplemental

Part Seven

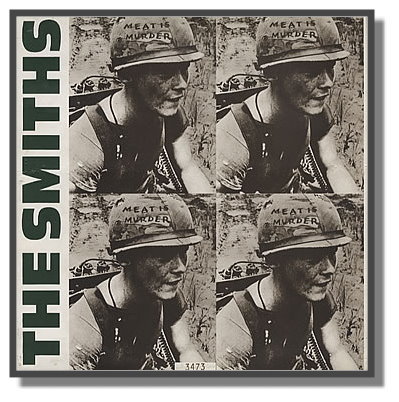

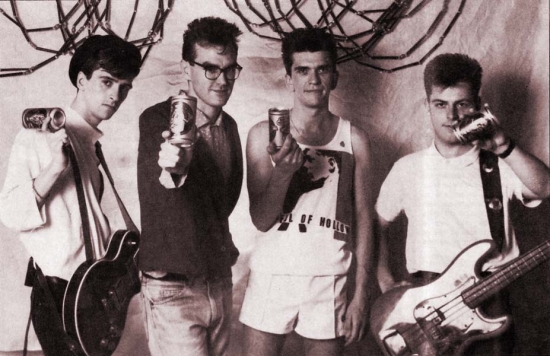

Photo of The Smiths by unknown photographer. Reproduced without permission.

This intriging item takes a look at the sequencing of the four Smiths studio albums. The uncredited author considers how the individual albums might have been improved with alternate sequencing and the dropping of certain tracks in favour of non-LP singles. A refreshing and irreverent treatment of Rock's most hallowed discography.

Dispelling The Myth:

The Smiths

Easy, Smiths fans and Morrissey acolytes, you can sheathe those daggers. I’m not going to court vitriol by penning a cheap tirade claiming The Smiths as "overrated" or by lambasting the hordes of Moz followers for their miserable, mopey dispositions. It’s been done to death and truth be told, it would be dishonest of me in the first place. I happen to believe that the Smiths were arguably the finest band of the 1980s, and for me to renounce them would be to negate literally years of my childhood spent obsessing over every note of their music. What I would like to address here is the conundrum I find myself in when someone asks what my favorite Smiths record is, or which album one should start with if exploring the band’s discography for the first time. A few months ago there was a listmaking exercise floating around the blogosphere where writers named a favorite album for each year they’ve been alive, and I was puzzled by the inclusion of so many Smiths records that occupied various slots of the ‘80s. The reason is an intangible quality that is rarely discussed in analyses of pop music album structure and content, yet is undeniably critical to a record’s effectiveness and how it’s assimilated by the masses. I’m talking about song sequencing.

Let’s get the obvious out of the way: in their six years of existence, The Smiths never pretended to be anything other than a singles band. The four official studio albums and three compilations released while the group was together were merely vehicles for their impeccable run of singles at the time, and to view full-lengths like Meat Is Murder (1985) or Strangeways, Here We Come (1987) solely as cohesive artistic statements is naïve at best and at worst, a serious disservice to everything Morrissey and Marr’s vision was about. I have a theory that the reason why the band split in the fall of ’87 wasn’t because of Marr’s frustration with the band’s direction or the endless curse of piss-poor management that plagued the group since their inception, but rather that no one ever sat them down and said, "Ok, gentlemen, these are the songs you should choose and this is the order in which they should be." I’m half-joking, of course, but in my perfect-world scenario, the following is how I would have altered the fabric of history by suggesting these changes and modifications to The Smiths’ four studio releases, assuming that I wasn’t, you know, like nine years old at the time of the band’s heyday.

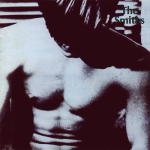

I don’t even know where to start with the self-titled debut. The argument of, "They were still a young band just gaining their footing," can only carry so much weight here. Putting aside the dry and unbalanced mix from producer John Porter, The Smiths (1984) is easily the most poorly-sequenced item in the group’s oeuvre. So many phenomenal songs could have kicked off the album: first single "Hand in Glove," the brooding and majestic "What Difference Does It Make," or "This Charming Man," which holds my vote as the finest single of The Smiths’ career, featuring a five-second introductory lead by Marr that’s one of the greatest things I’ve ever heard anyone play on guitar. But not only did the band choose the six-minute, mid-tempo dirge "Reel Around the Fountain" as their announcement to the world (a song which, granted, I absolutely fawn over), but they followed it up with the two worst songs on the record, one of them ("Miserable Lie") qualifying as the worst four and a half minutes the band committed to tape ("Golden Lights" notwithstanding). It isn’t until halfway through the record that The Smiths begins to pick up steam, although the placement of "Still Ill" between "This Charming Man" and "Hand in Glove" never quite gels. And even as closer "Suffer Little Children" begins to fade, the sins of the first half are still fresh in the memory. My suggestion? Eliminate "Miserable Lie" altogether and arrange the selections thusly:

1. This Charming Man

2. You’ve Got Everything Now

3. What Difference Does It Make?

4. The Hand That Rocks the Cradle

5. Still Ill

6. Hand in Glove

7. Pretty Girls Make Graves

8. Reel Around the Fountain

9. I Don’t Owe You Anything

10. Suffer Little Children

The Smiths’ follow-up, Meat Is Murder (1985) is a vast improvement over the debut and a bit of an anomaly in the band’s discography, as the one single culled from the record, "That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore," fared poorly on the charts ("How Soon Is Now" was added onto the US versions of the record); it’s the most "album-like" of the group’s studio releases. Despite being my least favorite item in The Smiths’ catalog, I actually don’t have any issues with the sequencing here; any record that opens with something as sonically dense and uncompromising as "The Headmaster Ritual" gains immediate favor in my book. My issue with Meat Is Murder is the inclusion of three lackluster songs – the trivial rockabilly romp "Rusholme Ruffians," utter afterthought "What She Said," and the disdainful, miserable, barrel-scraping title track (I’ve always loathed this song, even when I was a practicing vegetarian) – that could have easily been replaced by three singles that preceded the album’s release: "Shakespeare’s Sister ['Shakespeare's Sister' wasn't released until March, while 'Meat Is Murder' was released in February - BB]," the iconic "Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now," and "William It Was Really Nothing." One can only imagine the possibilities of an album where the hypnotic and propulsive "Barbarism Begins at Home" is the final layer of icing on the cake:

1. The Headmaster Ritual

2. William, It Was Really Nothing

3. I Want the One I Can’t Have

4. Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now

5. That Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore

6. How Soon Is Now?

7. Nowhere Fast

8. Well I Wonder

9. Shakespeare’s Sister

10. Barbarism Begins at Home

Ah, The Queen Is Dead (1986). The Smiths’ undeniable masterpiece, their singular, defining statement that solidifies their place in the pantheon of pop music. Naturally, I call bullshit. There are moments of perfection here – the psychedelic density of the opening title track, the achingly gorgeous "There Is a Light that Never Goes Out," Andy Rourke’s bass work on pretty much everything – but the entire first half of the record takes an enormous stumble that it never fully recovers from, beginning with "Frankly, Mr. Shankly." "I Know It’s Over" dangerously borders of self-parody and fails at the epic heights it attempts to attain, but even worse is "Never Had No One Ever," which is so similar in mood, tempo, and even pulse (6/8) to its predecessor that it’s genuinely shocking that no one pointed out this lapse in judgment when the band was sequencing the record. And sorry, but the literary pap of "Cemetry Gates" has always annoyed me. Side two immediately seems more promising with the one-two punch of "Bigmouth Strikes Again" and "The Boy with the Thorn in His Side," but the album’s momentum is hiccupped again with the quizzical "Vicar in a Tutu." "There Is a Light" could very well be the greatest song Morrissey and Marr ever penned and is not only quintessential Smiths, but the strongest contender for Best Album Closer in their catalogue. Instead, the band tacks on "Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others," the very definition of a b-side if I’ve ever heard one, to bring the album to its conclusion. Huh? The lack of singles recorded prior to the album’s release prevents the ‘supplemental singles’ method I utilized on "Meat Is Murder," so I’m afraid that this is the best I can do:

1. The Queen Is Dead (Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty)

2. Frankly, Mr. Shankly

3. The Boy with the Thorn in His Side

4. Cemetry Gates

5. Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others

6. Bigmouth Strikes Again

7. Never Had No One Ever

8. Vicar in a Tutu

9. I Know It’s Over

10. There Is a Light That Never Goes Out

Which brings us to The Smiths’ swan song, Strangeways Here We Come (1987), a flawed but nonetheless compelling album that’s generally regarded as most fans’ least favorite entry in the discography. The chief problem with Strangeways is that its second half pales in such comparison to the first that the band should have lopped it off altogether, designated it as an EP, and simply called it a day. Instead, the listener is treated to "Unhappy Birthday," which sounds like an outtake from Morrissey’s tepid Kill Uncle (1991), the never-ending record company rant "Paint a Vulgar Picture," and the almost embarrassing Moz confession "I Won’t Share You." The first six songs are exceptional and some of the best of the band’s career, but are sequenced so haphazardly that Strangeways begins to take on the guise of a post-disbandment compilation of outtakes and b-sides – and why on earth did they choose to open side two with "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loves Me"? Even substituting the last four tracks with singles still involves a lot of surgery here:

1. A Rush and a Push and the Land Is Ours

2. I Started Something I Couldn’t Finish

3. Stop Me If You Think You’ve Heard This One Before

4. Ask

5. Death of a Disco Dancer

6. Panic

7. Girlfriend in a Coma

8. Shoplifters of the World Unite

9. Sheila Take a Bow

10. Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me

Ultimately, of course, this is an exercise in futility for the diehards, but for the rest of us, a little juggling and switching can make quite a difference in enjoying The Smiths’ catalog. So what would I judge to be the quintessential Smiths album and ideal primer? My answer would be a resounding, blasphemous Singles (1995). Oh, the horror!

floodwatchmusic.com, October 29, 2008

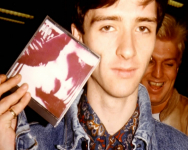

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo of Johnny Marr by unknown photographer. Reproduced without permission.

This brief reassessment of 'Meat Is Murder' considers how the album is important to the Smiths' overall musical and lyrical development. A necessary reappraisal for an album often dismissed as a mere holding pattern for the group.

Originally appeared in Stylus Magazine, September 1, 2003.

On Second Thought:

The Smiths - Meat Is Murder

For better or worse, we here at Stylus, in all of our autocratic consumer-crit greed, are slaves to timeliness. A record over six months old is often discarded, deemed too old for publication, a relic in the internet age. That's why each week at Stylus, one writer takes a look at an album with the benefit of time. Whether it has been unjustly ignored, unfairly lauded, or misunderstood in some fundamental way, we aim with On Second Thought to provide a fresh look at albums that need it.

The Smiths was released in 1984 to general disappointment. Lazy production and haphazard structure consigned an album expected to be a definitive work to a level lower: a band capable of a masterpiece, in time. This, the follow up, was the fulfilment of that promise, bursting with vigour and variety. It announced The Smiths on the music scene as a talent capable of a masterpiece - a talent that would endure to make them the greatest British guitar band of its time.

"The Headmaster Ritual" announced the New Smiths’ arrival with intent. A vitriolic swipe at institutionalised cruelty in Manchester schools, labelling their heads "spineless bastards" may well have seemed like a safe move geared at their stereotyped fan-base of bedroom dwelling tortured teen souls, but the conviction of Morrissey’s words and delivery makes it applicable to anyone resentful of a figure of authority, be it boss, politician or otherwise. Johnny Marr’s intricate guitar work is not constrained by clumsy production as it was on the debut and this opening track is a guitar master-class.

There was no great thematic departure at any point in the career of the band and Meat is Murder is no different. Morrissey is still by far his most affecting when he is recoiling. "When you laugh about people who feel so very lonely their only desire is to die, well I’m afraid it doesn’t make me smile" he laments on "That Joke isn’t Funny Anymore". Charting the complexity of emotions felt at the end of a relationship and how the world seems a different and less accommodating place without someone you love than when with them, the enigmatic lyrics allow the listener to make it as revelatory as they choose. "On cold leather seats it suddenly struck me, I just might die with a smile on my face after all", a reference to being in the midst of a maniacal and ultimately suicidal drive? Or perhaps something more elicit? Morrissey famously described how erotic he finds leather upholstery in a NME interview, a strange inclination at any time but particularly for such a passionate vegetarian and champion of Animal Rights, but that’s Steven Morrissey for you.

It is this motivation that fuels the album’s call to arms - the title track. It caused fans to convert to vegetarianism in their droves and others deny it as overly melodramatic - either way there is no denying its fervour and commitment to the cause by Morrissey, condemning meat eaters as murderers. The Queen is subject to equal abuse on "Nowhere Fast"; despite the comical nature of the line "I’d like to drop my trousers to the Queen" it develops into a stinging assault on the monarch. "The poor and the needy are selfish and greedy on her terms" is the diagnosis, an indication of the direction they would take on the follow up album.

Inspiration comes from a wide range of sources. "Rusholme Ruffians" evokes Victoria Wood’s "Fourteen Again" and Pomus & Shuman's "Marie's the Name (Of His Latest Flame)", a song it would segue into when played live. The northern comic’s verbose style is imposed onto a song made famous by Elvis Presley to superb effect. Andy Rourke’s wandering bass-line helps dispel the myth that the Smiths were Morrissey, Marr and "two others", though admittedly it is Morrissey’s jaded line "Someone falls in love, and someone’s beaten up, and the senses being dulled are mine" that proves its most enduring memory.

The lyricist’s fascination with Elizabeth Smart’s sublime novel By Grand Central Station I Sat Down And Wept that fuelled "Reel Around The Fountain" is even more evident in the bouncing "What She Said". Lines like "I smoke because I’m hoping for an early death" and "How come someone hasn’t noticed that I’m dead" are reconstructions from the book that are made for the purpose of describing in-depth the plight of a depressed and self-involved woman. The song also seems to owe a debt to the Beatles song "She Said, She Said" from Revolver that stretches further than the title.

Sexual ambiguity rears its head on "I Want The One I Can’t Have", hitting out at a closet dweller in denial: "On the day that your mentality, catches up with your biology, come around" may not be his most implicit reference but its subtlety is typical of the complexity that runs through this record. It is only on the blunt and overlong "Barbarism Begins At Home" that the LP suffers a dip in quality.

Whether it is staring out of your bedroom window to the sound of "That Joke..." or bouncing down the street to "What She Said", The Smiths craft music that makes you feel totally safe but frighteningly vulnerable at the same time. They deserved to transcend the patronising categorisation they suffered at every juncture of their career, and no record documents their diversity better than this.

Jon Monks

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

And finally... this excerpt from 'The Smiths - The Tatty Truth' in Incendiary Magazine, June 1, 2008. Words by Michael Evans.

Meat is Murder is the bridge between early-Smiths and late-Smiths containing some of the raw energy of early recordings and the intricacy of later ones and its production is far improved over The Smiths. Johnny Marr's guitars rarely ever stray from the sublime and this record is a testament to his ever increasing ability and range of styles from the Elvis pastiche of 'Rusholme Ruffians', the rocking out on 'What She Said' or the understated acoustic melancholy of one the Smiths most underrated tracks, 'Well I Wonder'. Lyrically, Morrissey steps up a gear and delivers his most potent set of lyrics to date managing the classic Morrissey trick of being both frighteningly serious and hilariously funny in the same song. In style too he's progressed from the early monotone to varying pitch, delivery, style and even throwing in a whole host of shrieks and yelps. Even the 'forgotten Smiths' play a vital part be it the thunderous drumming of Mike Joyce on 'What She Said' or Andy Rourke's bass work, which is never less than brilliant throughout.

And while the funk ending of 'Barbarism Begins at Home' or the melodrama of the title track might not be too everyone's tastes this is by and large an excellent album. As ever, it takes a few listens to get into and get over the fact that The Smiths never were that keen on silly things like choruses but its well worth the effort.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

SEE ALSO: Uncut Classic - 'Meat Is Murder'