BEGINNINGS

Pre-history and early days

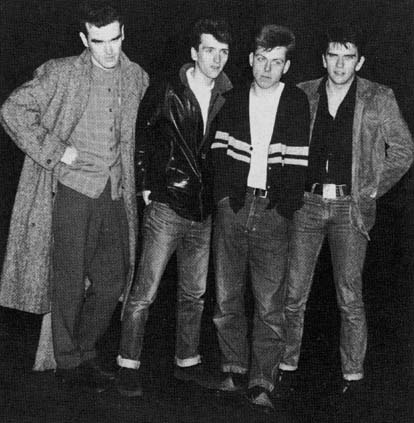

Photograph of the Smiths by unknown photographer. Reproduced without permission

Originally appeared in the February 1983 issue of i-D magazine

The following item originally appeared in the May 1985 issue of The Face. One of the first articles to delve into the pre-history and early days of The Smiths.

Dreamer in the Real World

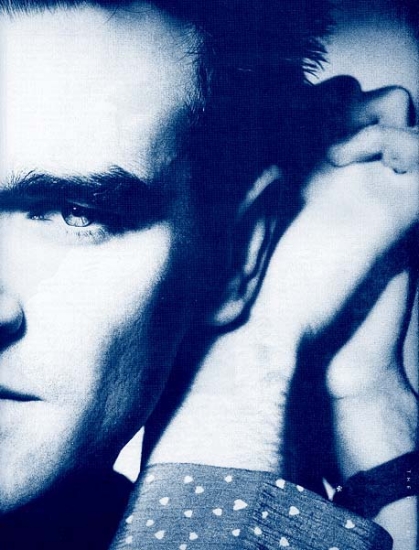

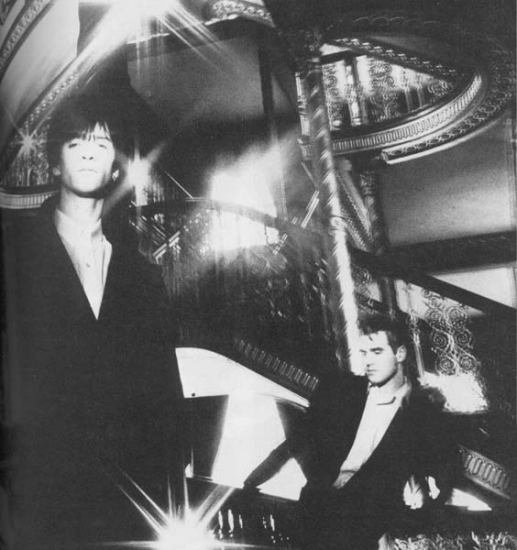

By Nick Kent Photographs Nick Knight

To his father, he was a "complete fruitcake," to his contemporaries "the village idiot". Yet in the treacherous image-bloated clone-zone of pop, his is the voice that speaks out against a tide of rabid conformity. But what if all Morrissey's candour merely hides his own insecurity and doubt?

THE CALL CAME FROM The Smiths' London HQ. On the line were the parched, middle-American tones of Scott Piering, the group's ersatz manager.

"Ah Nick, I really don't quite know how to broach this because... ah, see, I'm sure you're not... Well, I'm convinced you're an ally and you've clearly put a massive amount of thought and research into your story but... erm... that's why concern is so rife."

"It's Morrissey, you see. He's discovered that you're talking to a number of former acquaintances, a couple of whom he considers to be arch enemies. I've been getting frantic calls from him. He desperately wants to know what was said about him because he fears that at least one of those people might misrepresent him, kind of. I know this seems rather petty but he's just very, very concerned. He would rather clear up your queries personally. Could you call him on this number? I know he wants to talk to you. Ah... one thing. He might not answer the phone at first because, as you've probably gathered, he is very, very shy but if you could try..."

In due course I try, requesting the receptionist at the Kensington hotel to page a 'Mr. Morrissey'. ("First name please?" she asks. "Yes. Mr. S. Morrissey.")

The phone rings but to no avail. Seven digits later, the voice of Morrissey appears: calm and collected but a mite terse in its disembodied Mancunian mode of addressing the matter in hand.

"I've been hearing rumours that you've talked to several people about my past. Is this so?"

I reply in the positive, naming names.

"I am very concerned about what they said because at least one of them is a sworn enemy who would get no small quotient of pleasure from wilfully misinterpreting my activities, I'm afraid to say."'

I argue that nothing truly scabrous emerged from any of these dialogues, but Morrissey will not be swayed. His manner becomes officious.

"Could I see what you've written as soon as possible?"

I concur, arranging to meet two days hence. And I am left once again utterly bemused by the disarming effect of this decidedly skittish but steadfast young obsessive.

AT THE OUTSET, EVERYTHING seemed so appealing in its apparent simplicity. After too many seasons of feeling diffident and relatively untouched by contemporary popular music, along came The Smiths in time to forestall a last cold cut from the moorings of pop culture fascination.

Their initial performances - "those absurd celebrations" that Johnny Marr now reminisces over so fondly - took place in my absence. It only struck home on hearing the group's first album. This was not more self-absorbed bleating in an aural wasteland of recycled clamour. This was something else.

Morrissey's audaciously crooned insights and Johnny Marr's plangent guitar voicings were the most orthodox of ingredients. Spiritually enhanced by sounds and sensations born of the Sixties, this music possessed something far more scarce. The Smiths had gathered all that was inherently noble about a rich verdant age and applied these characteristics to the morose and desperate present.

After the regressive thuggishness that punk so quickly came to personify, followed by the worthless bourgeois values of the current pop hypermarket where business acumen and its attendant creed of material wealth appears to be more virtuous a concern than artistic ingenuity, I find myself empathising with guitarist Marr's description of The Smiths as "the only truly controversial and important band of the Eighties."

Clearly, it was high time the tale of this band be told, and not just via the typical amateur question-and-answer bout with the frail, ever quotable Morrissey. How did this figure, for a long time regarded as "the village idiot" by other Manchester luminaries, rise to such prominence? What are the events that shaped the sensiblity at work in the songs? More pertinent still, does Morrissey really care about misfits, the people with whom he has struck such a chord?

For answers to questions like this, you would have to seek out the likes of Joe Moss, the owner of Crazy Face, a Manchester boutique where a teenage Johnny Marr once worked. Moss was a considerable influence on Johnny Marr's musical tastes, if only through granting him unlimited access to a formidable record collection. He also alerted the young guitarist to the burgeoning reputation of a local enigma best known for his tenure as New York Dolls fan club president, one Steven Morrissey.

In fact, Moss was The Smiths' manager during the first six months or so of their career - until, according to a Rough Trade spokesperson, "it became apparent that he was getting further and further out of his depth". But at least Moss's presence in the precincts of Smithdom is attested to (he crops up in some of the very first music features on the group and, despite the protests of one group member, has a note of gratitude engraved to him on the sleeve of the "Hand In Glove" 45).

Not quite so fortunate was young James (no relation to the group of the same name who continue to support The Smiths in concert). He was the male 'go-go dancer' whose stiletto heels and maraccas augmented the first-ever Smiths stage line-up. Unfortunately, audience reaction was so rampantly antagonistic towards this precocious spectacle that James was fated to vanish from history as suddenly as the group's bass player for a spell in late 1982. This certain Dale, a recording studio engineer, was employed, according to Johnny Marr, merely to force the wayward Andy Rourke's attentions towards a true commitment to the group.

The full Smiths story would also be serviced by the comments of Factory Products supremo Tony Wilson (a long-time Morrissey admirer, though he passed up the chance of releasing their product) and former Buzzcocks manager Richard Boon whose recollections of Morrissey stretch back to the small ad that appeared in Sounds some ten years ago. Then there are former proteges Ludus - more specifically the group's singer Linder (as she chooses to spell it). Linder, it is agreed by all who witnessed the peculiarly insular and brooding manoeuvres of Steven Morrissey circa 1978-79, had a pretty severe effect on the young aesthete.

Add to that list the formidable Mrs. Dwyer, mother of Morrissey who reverted to her maiden name some seven years back (when she and her husband finally took their irreconcilable differences to the divorce court) with the same single-minded finality of purpose her beloved son displayed when he severed his own Christian name(s), and one could feel that the waterfront is being gumshoed.

Yet the process of using other people's recollections to establish a more objective focus is anathema to Morrissey. In fact, he turns quite ashen at the suggestion.

"I would hate that. I honestly believe that ploy never works, because it's like trying to prove that somebody is - to some degree - a fake. The past always tends to seem a little embarrassing even though at the time it was anything but... And it's like saying 'Well, you might be this now but don't ever forget that you were once that. You used to do this and you bought this awful record and you thought it was wonderful.'

"You see, I can describe the key incidents as far as I was concerned. I recognise them very clearly. This might not wash but the key incident for me was that I never had any real friends. And I realised that in order to have friends and impress people, I had to do something extraordinary.

"In a way, it's a type of revenge. You hate so many people... It sounds very juvenile now, I suppose, like smashing someone's window. But then what else can you do? It was like a weapon, something to make them gnash their teeth. Otherwise people will always have the finger on you. Always."

REVENGE. ISOLATION. ABSOLUTE self-conviction. Mistrust... At least Morrissey's rhetoric is constant. But study the words and deeds of this curious individual whose every spark of unfettered candour has kept the music press enthralled throughout the two mercurial years of The Smiths' existence and one can only conclude that here is a man whose convictions tend to waver in certain key areas as mysteriously as they remain consistent in others.

"He tends to vacillate terribly," one associate concludes, pointing to Morrissey's love/hate relationship with Manchester, site of all his most wretched spells of inner turmoil. In the past, he would aim frenzied gobs of invective at the Northern metropolis, vowing to escape the blighted wasteland of his youth at the earliest moment. Nowadays the Mancunian environment is deemed inescapably "precious", with both its former captive and his songwriting partner eulogizing the North as the crucial source of inspiration for their music. Both Morrissey and Marr stress how essential it was that sessions for their second LP, "Meat Is Murder," took place in Liverpool's Amazon studios amidst earthy Northern badinage as opposed to studios in London where they were made to feel like nuisances and timewasters in the proximity of lavish multi-track equipment.

Indeed, ask any of the coterie at Rough Trade whose job it is to abet The Smiths' maverick journey over and around the black hole of pure pop fun and after due homage has been paid to the group's 'brilliance' and 'commitment' (no videos, no megabuck ad campaigns, no flim flam) even a stalwart like Geoff Travis of Rough Trade will finally admit that their insularity has caused considerable problems. Manager Scott Piering declares himself "utterly won over by the results. In almost every instance, they have proved themselves right." His assistant Martha Defoe however criticises what she calls an "extreme naivety" on their part. "There have been occasions when they've been influenced by certain parties that anyone else in this business wouldn't give houseroom to."

Add to this the not infrequent phone calls of Mrs. Dwyer, doting mother of Morrissey who, since her retirement as a librarian, virtually lives for her son, viewing his career in an industry that is "full of sharks" with extreme concern. Travis in particular has found himself having to placate this formidable woman's accusations that all he and his record company are interested in is making as much money as possible out of her flesh and blood's sweat and strain.

GEOFF TRAVIS IS CLEARLY besotted with The Smiths. And for every frustration there is a bonus potentially as vast as that very first time when, having witnessed an early Rock Garden performance unmoved, Travis was cornered in the kitchen of Rough Trade's old West London offices by Johnny Marr and bassist Rourke and forced to listen to a demo of "Hand In Glove," financed by Joe Moss.

"I remember Johnny glowing with pride saying 'This is it! Just listen to this.' I was helplessly won over."

Since that time Rough Trade have lost their three most formidable pre-Smiths acts - Aztec Camera ("Roddy Frame's ambitions were simply too grand for us"), Scritti Politti (ditto Green's recording bills) and The Fall. Here was a conflict of interest, whether Travis, the eternal music-loving idealist, saw it or not. Certainly he perceives Fall leader Mark E. Smith as a figure "who will always consider himself the spokesman of the Northern roots culture, a culture centered in Manchester". He recalls the tenacious Mark Smith voicing extensive grievance over RT's desires to seek "pop perfection," an obvious jab at that other Mancunian group who had after all started out supporting The Fall.

"I remember," adds Travis, "one incident when Mark was present in the office and quite by chance Morrissey appeared to talk business. Mark just fixed him with this very sardonic look and said quite clearly - 'Ah, hello Steven!' Morrissey was visibly shaken by it."

Quizzed about the severing of Steven from his monicker, Morrissey simply states: "I just found that when people addressed me by my surname I felt differently about myself and that difference moved me to decide that I wanted to be called Morrissey permanently. I just felt this absolutely massive relief at not being called Steven anymore."

Perhaps it would have been different had Steven Patrick Morrissey, born 22/5/59 into a working class family - father (a hospital porter), mother (a librarian) and sister Jacqueline then living in Hulme, Manchester - not already gained a bush league infamy for himself as a local bohemian and eccentric writer of letters. These, turning up in the odd fanzine, eulogized the Buzzcocks, James Dean and The New York Dolls. Earlier, at the age of 12 but with the same obsessiveness, he had fired off reams of scripts for Coronation Street.

LIFE, ACCORDING TO MORRISSEY, was agreeable enough up to the age of seven or eight when two significant events took place. One was the first spate of discord between Steven's parents that would end in divorce ten years hence.

The other was, if anything, even more traumatic to a seven-year-old with an imagination that, while others opted for Bus-bars and Sherbet Dips, seized on the barbaric rituals of those dissolute (often male) and helpless (often female) types drawn to the Manchester fairgrounds of the late Sixties in search of love-bites and knife-wounds "under the shield of the ferris wheel" ("Rusholme Ruffians" relates just such a child's exposure to the mindless thuggery the grown-up Morrissey so abhors.)

In 1966, Ian Brady, a Glaswegian transplanted to Manchester, and his secretary and mistress, a Mancunian named Myra Hindley, were sent to trial on charges of procuring, torturing (sexually and otherwise, often photographing and taping the atrocities) and ultimately murdering one nine-year-old boy, an 11-year-old girl and a 17-year-old youth. Two other youngsters also went missing at the time. The case is dealt with in Emlyn Williams' book Beyond Belief. Williams shuns any sensationalism; the tabloid press of the time did just the opposite, transcribing scream after taped scream from the courtroom playbacks. The whole of Manchester was stunned and seven-year-old Steven Morrissey was more than averagely susceptible.

"I happened to live on the streets where, close by, some of the victims had been picked up. Within that community, news of the crimes totally dominated all attempts at conversation for quite a few years. It was like the worst thing that had ever happened, and I was very, very aware of everything that occurred. Aware as a child who could have been a victim. All the details...

"You see it was all so evil; it was, if you can understand this, ungraspably evil. When something reaches that level it becomes almost... almost absurd really.

"I remember it at times like I was living in a soap opera..."

BY THE AGE OF NINE, the child had become a distinct problem. His father he rarely if ever refers to, but once let slip that the former considered his only begotten son a "complete fruitcake" during those years of intense brooding. His mother, however, saw an artistic bent in her son's otherwise perplexing quasi-inertia. A librarian, she introduced him to the works of Thomas Hardy and Oscar Wilde, the latter sparking an infatuation that persists to this day. It was then that Coronation Street took hold of the boy. Morrissey's scripts laced with suggestions for character and plot so impressed producer Leslie Duxberry that he began a correspondence with the callow youth who had an extraordinary backlog of trivia about the series.

And then there was music. He bought his first disc at age six - a year before Hindley and Brady's gambols on the moors turned life into a soap opera of mind-numbing horror. The record featured the virginal entreaties of a pristine Marianne Faithfull singing "Come And Stay With Me". The mild sexual overtones of the lyric went well with the halcyon blend of folk guitar and baroque pop. Indeed, Ms. Faithfull was Morrissey's first love and in a world where first loves never die it is intriguing that the only two non-originals The Smiths have attempted were her "Summer Nights" (a thrilling harpsichord-led piece that foreshadows some early Smiths songs) and "The Sha La La Song". Quintessential British pop, an influence either due to the radio or elder sister Jacqueline or his own simple rationale: "I was brought up in a house full of books and records... I devoured everything."

Though he found himself "disgusted by the savagery of fun fairs I went to in the Sixties" he sought out music that embodied that atmosphere: the treble-and-reverb lamentations of Billy Fury, king of the fairground swing. Similarly a cute doily of a song, The Tams' "Be Young, Be Foolish, Be Happy" he has always cherished "because of the sentiment. Not that I could ever relate to it. But then maybe that's why I found it so appealing in the first place."

Morrissey's placement at St. Mary's Secondary Modern was, from all reports, the worst fate for one of such haphazardly zealous temperament. He found a place, but not by reciting Oscar Wilde or displaying his growing aptitude for the written word. "I happened to be very good at certain sports. I was really quite a fine runner, for example. This in turn made me act in a somewhat cocky and outspoken way - simply as a reaction against the philistine nature of my surroundings. This the masters simply couldn't take. It was alright if you just curled up and underachieved your way into a stupor. That was pretty much what was expected really. Because if you're too smart, they hate and resent you and they will break you. When I found out that I wasn't being picked for the things I clearly excelled at, it became a slow but sure way of destroying my resilience. They succeeded in almost killing off all the self-confidence I had."

Music again offered escape and excitement. Early in 1972, at the age of 13, Morrissey witnessed his first live gig: Marc Bolan's T. Rex at Manchester's Bellevue Theatre. "All the kids at my school were either into Marc Bolan or David Bowie," he recalls. "You couldn't like both of them." But it was the New York Dolls who were "The real beginning for me. They were so precious...

"Rock and roll - the traditional, incurable rock and roller never interested me remotely. He was simply a rather foolish, empty-headed figure who was peddling his brand of self-projection and very arch machismo that I could never relate to. The Dolls on the other hand... well firstly I always saw them as an absolutely male group. I never saw them as being remotely fey or effeminate. They were characters you simply did not brush aside, like the mafia of rock and roll."

Upon falling out of St. Mary's into the outstretched arms of the dole queue in 1975, Steven Morrissey's life appears to have revolved around the music of the New York Dolls and Sixties girl singers, the crucial "symbolic" importance of James Dean and the continuing lure of the written word. He claims at 14 to have been initiated into the doctrines of feminism, citing a book titled Men's Liberation as shaping what has since become a key concept in his own lyrical observations. But it was the New York Dolls connection that afforded him a certain notoriety. His small ads in the music press seeking to swap fax and info with fellow Dolls fans caused him to be one of the few ersatz personalities in the punk explosion that hit Manchester, the first stop of the Sex Pistols' infamous 'Anarchy' tour, in 1976.

"With punk I was always observing. I mean, I seem to recall being a spectator at almost every seminal performance in the movement's evolution especially in the North. But the aggression was just 'bully boy' tactics. It was, I feel now, a musical movement without music. I mean, how many records were really important? How many can be remembered with fondness? Not many...

"The Ramones' first album I recall as one. Also the Buzzcocks, who, I must be honest, seemed, out of this massive sea of angst-ridden groups, the only ones who possibly sat down beforehand and worked out what they intended to do."

By this time it would be fair to assume that Morrissey had genuine musical ambitions. His main obstacle, apart from a shyness that was "criminally vulgar" was his fear that a rock music backdrop would place him "in circumstances where I would be a very... timid performer."

Perhaps, then, he would be temperamentally more suited to music journalism. Turned down no less than five times by a certain NME section editor, he went on to supply record reviews to Record Mirror under the nom-de-plume Sheridan Whitehead. Various punk fanzines were also created by him, and he is remembered by Richard Boon as being a frequent visitor to Buzzcocks' office. In 1978, due possibly to his parents' final rift, Boon recalls Morrissey becoming extremely close to the group Ludus, principally the singer Linder, for whom he seemed to be nursing a growing infatuation.

Linder was deeply affected by the work of certain feminist writers and was prone to carry around such tomes as Geneology and The Wise Wound. Morrissey duly moved in with Linder and Ludus guitarist Ian to a less than salubrious abode in the red light area of Whalley Range where they lived for approximately a year. This is the inspiration for the "What do we get for our trouble and pain/A rented room in Whalley Range" couplet that lyrically climaxes the pummelling frenzy of "Miserable Lie" from the first album and remains a live show-stopper. Indeed, one could read more than enough about the nature of Morrissey's relationship with Linder in the song's complete lyric. Similarly, certain sources intimate that "Wonderful Woman" and "Jeane" stem from this relationship.

WHATEVER THE CASE, MORRISSEY and Linder parted on good terms and their friendship remains constant, with the former helping to promote the re-formed Ludus' product whenever he's afforded radio-space. More pointedly, Morrissey's avowed celibacy usually dates from around 1979.

Straight after leaving Whalley Range, Morrissey seems to have vanished for several months, informing certain acquaintances that he was going to New York. Events here begin to take on a less clear-cut aspect, due in part to a penchant for imposture and self-conscious myth-making that recalls Bob Dylan's tangle of false trails across his folkie past.

Marr recalls, at any rate, that the makeshift group he sometimes rehearsed with tried to coerce Morrissey into becoming their frontman. But the only pre-Smiths venture that Morrissey admits to is a short-lived one.

"There was always an obvious ideological imbalance with whoever else approached me. The one occasion I walked into this group as a potential singer, I said - the very first thing - let's do 'Needle In A Haystack' by The Marvelettes. These were four individuals who seemed in tune with this mode of thinking. It wasn't 'camp surrealism' or 'wackiness,'' it was pure intellectual devotion that made me want to do a song like that."

Perhaps it was this ensemble that Howard Devoto swears he witnessed supporting Magazine in a Manchester club. Devoto doesn't recall much: a guitar, drums and bass line-up, with Morrissey singing while lashing his hair out of his eyes. And so it goes. If it happened at all, it was short-lived.

"The main reason for my not being able to do anything really constructive before Johnny's arrival," Morrissey now concludes, "is that with all the desires I had been harbouring for years, if anyone else existed out there who shared the same creative urges, that person was invariably incredibly depressed, totally disorganised and somehow unsalvageably doomed. In other words, a complete slut."

Richard Boon recalls the last pre-Smiths utterance from Morrissey. This came in 1980 in the form of a demo tape on which was recorded, firstly, a spoken apology for both the lack of any backing instruments and the low fidelity of Morrissey's vox humana. This was due to the fact that someone was asleep in the next room. Of the two songs he definitely remembers hearing, one was a version of "The Hand That Rocks The Cradle" sung to a different melody. The second was a truly ironic choice. Just two years before Marr would come and pull our ailing hero out of some sick sleep and into a partnership that would prove providential, the gaunt Mancunian had chosen to interpret a little-known Bessie Smith number. Its title? "Wake Up Johnny."

If it's time the tale was told, then let the teller be Johnny Marr for if The Smiths remain Morrissey's mouthpiece then just as surely the group is Marr's contrivance and their strength lies in the guitarist's ability to create a consistently inspired musical setting every bit as aurally valorous as the lyricist's formidable confessions.

When one confronts them together, their age difference and clearly defined visual contrasts make them appear almost like teacher and pupil. Morrissey's expression furrows from laconic to austere whilst Marr's face, even when drawn into discussion about matters that are anything but frivolous, can't quite lose the hint of mischief etched onto its ever-increasing jackdaw pallor.

More pertinent perhaps are the silent exchanges. Marr on the first occasion the three of us met was chipper but, shorn of sleep, seemed occasionally too quick to answer without having focused his reply, the latter faculty being one of Morrissey's most masterful verbal ploys. Yet if Morrissey's candour seems sometimes measured with an inscrutable sense of being able to almost instantly see the quote in print, then Marr's frankness is refreshingly absent of this concern. When Morrissey aims to wax controversial he spares no drop of venom in the process. Marr is simply more open. Also Marr clearly holds his partner in the highest of esteem. A sense of pride and protectiveness, for example, causes remarks like this: "I don't want to sound cheap or false, but (slight pause) really I'm Morrissey's greatest fan. This is the absolute truth here now, I mean the fact of being involved in the only worthwhile and healthily controversial group of the Eighties, that was a big part of the original plan at first but now we've achieved it, it's just another facet.

"After working with Morrissey I could never even consider being involved with anyone I wasn't totally, 100% impressed and inspired by. It's like," Marr continues excitedly, "the very first time I got to see Morrissey's lyrics and the feeling I got of being completely stunned by them. There were just so many aspects: the subject matter, first of all, and the fact that every line was like a blow, a really straightforward blow. Every word had such real impact that once I'd recovered, it suddenly hit me that before this moment I'd never really listened to a lyricist before."

Morrissey, for his part, is no less complimentary. "When I first heard Johnny play, that was in a sense almost irrelevant. The awakening had occurred days earlier with the meeting. I'd reached a stage back then where I was so utterly impressed and infatuated that even if he couldn't have played it didn't matter somehow because the seeds were there and from those seeds anything could sprout.

"Johnny had grasped the thread of all that was relevant and yet he was - and remains - a very happy-go-lucky, optimistic person who was interested in doing it now. Not tomorrow, but right now!

"Now this was truly extraordinary because in a musical sense I'd only just met people who were total sluts, who'd rather sit around at home night after night talking about picking the guitar up instead of just grabbing it and saying 'What about this?'

"Also he appeared at a time when I was deeper than the depths, if you like. And he provided me with this massive energy boost. I could feel Johnny's energy just seething inside of me."

JOHNNY MARR WAS BORN IN Ardwick Green twenty one years ago. His parents are still together and he has a younger brother and sister. Unlike his more erudite co-composer he passed his 11-plus but ended up in a Comprehensive school - Withenshaw - where he found himself more interested in experimenting with the soft drugs that a predominantly older crowd of local musicians were introducing him to. He left school with no 'O' levels, a vendetta between himself and his father, and a 'friend' he'd been originally asked to keep an eye out for by the school's headmaster when the latter had discovered that "this posh kiddie with a chip on his shoulder" was courting a potential barbiturate problem.

The latter "posh kiddie" had been Andy O'Rourke at the age of 13. At the ages of 14 (when various friends and Marr toyed with the idea of working with a girl group) and 17 (when he and Rourke were again put off by "how bad everybody's lyrics were") attempts had been made to form bands. While holding down a job selling clothes for a store called X Clothes (next to Joe Moss' Crazy Face), Marr, who was able to retain his Les Paul guitar plus twin-reverb amp and his steady girlfriend Angie throughout the ensuing ordeal, somehow got in with some jewel thieves and was caught with some stolen Lowry prints. A heavy fine put paid to further escapades in crime, leaving Marr to finish up working in clothes stores until February 1983.

As for the relationship he has with Morrissey, when alone, the characteristic concern and intense loyalty come through - yet like Geoff Travis and Scott Piering and everyone else I spoke to about him, Marr is evidently as puzzled by his partner as I still am. The so-called enemies and people Morrissey felt would do him injustice didn't but that's only because there is no-one in the treacherous image-bloated clone-zone packed to the rafters with rent boys, vainglorious dupes and back-slapping careerists who can hold a candle to Morrissey and his Smiths. Instead, detractors attempt to dissect the true sexual urge that might lurk in the celibate's loins (and behind titles like "I Want The One I Can't Have"), or indulge in lazy critiques of music that addresses the real issues facing our pop kids - affording them a voice that speaks out against the tide of rabid conformity.

"He is painfully shy," emphasises Johnny Marr. "You've got to understand that. We all look out for Morrissey. It's a very brotherly feeling. When we first rehearsed, I'd have done anything for him.

"And as a person Morrissey is really capable of a truly loving relationship. Every day he's so open, so romantic and sensitive to other people's emotions.

"Personally speaking - I don't know this but yeah I think - I don't think he'd turn away from the perfect opportunity. But try and imagine the hang-ups most people have in bed. All that 'Is she enjoying it? Is there something more than this?' Confusion. Now magnify that a hundred times and you've got the beginnings of Morrissey's dilemma...

"But I must say that when he gets really upset, frankly I think it's just because he needs a good humping!"

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photos by Nick Knight reproduced without permission.

See the original article here