"I heard it on the radio..."

1995-1998:Part One

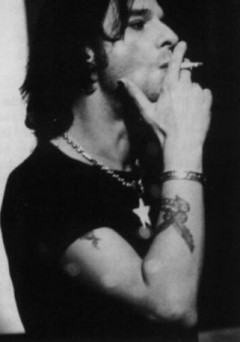

Dave Gahan after being released on bail, L.A., July 1996

Photo by Kerry Davies. Reproduced without permission

NEWS ITEMS The following two news reports date from September 1995 and detail Dave Gahan's suicide attempt and subsequent recovery. Dave Gahan Slashes Wrists in L.A.

Dave Gahan, singer with Depeche Mode, is recovering at home in Los Angeles after being released from hospital following a suicide attempt.

Gahan was rushed to Cedars Sinai hospital on Thursday, August 17, checking in under an assumed name. One report says he slashed his wrists and then called the police.

A detective from the West Hollywood Sheriff's department confirmed that Gahan, 33, was taken to hospital with lacerations to the wrists consistent with being slashed with a razor blade. He could not confirm that Gahan himself called 911, the emergency number.

The singer was kept in hospital to evaluate his mental competence before being discharged on Tuesday, August 22.

According to some sources, Gahan has been under severe strain. Depeche have all but split up; they haven't worked in the studio for two years and have not been touring. Andy Fletcher, one of the band's co-founders, quit the band earlier this year and Theresa, Gahan's second wife of several years, had walked out on him.

Mute Records claimed not to know the reason why Gahan was hospitalised. Depeche Mode have been on the label for nearly 14 years.

Andy Richardson

New Musical Express, 2nd September, 1995

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

Depeche Mode in recording studio

British synth-rockers Depeche Mode are laying down tracks in an English recording studio, the band's career apparently back on track after the departure of Alan Wilder earlier this year and subsequent suicide attempt of vocalist Dave Gahan.

People close to the band said Gahan is in the process of getting a divorce and is trying to kick his heroin addiction, the two factors behind his wrist-slashing incident.

"The vibe and the mood is very good," said one source. House/techno producer Tim Simenon is presiding over the sessions, on which former Living Colour bassist Doug Wimbish is helping out.

At this stage, it is not known if the tracks will make it to an album, or when an album will in fact come out.

Reuter, 30th November, 1995

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

This lengthy news item appeared in the 8th June, 1996 issue of New Musical Express and details Dave Gahan's drug overdose and subsequent arrest for drugs offences.

Going...Going...Gahan...?

Dave Gahan narrowly escaped death for the second time in less than a year last week.

Responding to an emergency 911 call at 1.15am on May 28, from an unnamed woman saying that she was Gahan’s roommate, deputies of the West Hollywood Sheriff’s Department and paramedics knocked down the door of Gahan’s room at the Sunset Marquis Hotel, Beverly Hills, Los Angeles.

They found the 34-year-old Depeche Mode singer unconscious in the bathroom. They also found a "sizeable amount" of what they believed to be a mixture of heroin and cocaine, as well as drug paraphernalia. Gahan was rushed to Cedars Sinai Medical Centre for emergency treatment where staff confirmed that he had been treated for a drugs overdose.

He was kept under police guard while in hospital and as soon as he was discharged, at 8.30am, he was arrested and taken to the West Hollywood Sheriff’s Station where he was booked for possession of controlled substances, a felony offence, as well as charged with being under the influence of a controlled substance, a misdemeanour. He was released at 12.30pm on $10,000 bail.

This is the second time in under a year that Gahan has been rushed to Cedars Sinai for emergency treatment. In August 1995, he was admitted to the hospital with "lacerations to the wrists consistent with being slashed with a razor blade", according to the Sheriff’s Department. Statements from Depeche Mode’s management and record company followed denying that Gahan had made a suicide attempt. Spokespeople for Gahan said that he had "accidentally cut his wrists during a party at his home". The Sheriff’s Department would not confirm whether it was Gahan who had dialled the 911 emergency number.

Shortly before the accident, Depeche Mode co-founder Andy Fletcher had left the band and Gahan had split with his second wife, Theresa.

Following the latest incident, Gahan’s record company, Mute, who have had the band under contract since 1981, have been tight-lipped about the singer. However, sources close to him do admit that he has problems. One American friend said that he doesn’t believe that the latest incident was a suicide attempt. He claimed Gahan had been undergoing treatment for drug dependency for at least two years, since the band came off their Devotional Tour in 1994.

Another source said that he had just come out of a 12-step drug rehabilitation programme, shortly before his overdose. If that is true it would suggest that the overdose was more likely to have been the result of an accident than a suicide attempt. Also, the presence of another person in the room with Gahan, the woman who called 911, would make a suicide attempt seem less likely.

The hospital would not confirm whether or not Gahan had been injecting the heroin/cocaine cocktail. In medical circles this combination is known as Brompton’s Cocktail and is sometimes administered to terminally-ill patients, particularly those suffering pain from cancer. Known colloquially as a ‘speedball’, the combination is favoured by many junkies because of the euphoria that the two drugs bring: the cocaine gives the user an immediate rush of energy, awareness and clarity while the heroin smoothes out the ‘comedown’ effects from the cocaine, which gives only a short-duration high. Many users inject larger quantities of ‘speedballs’ than they would of heroin, which can lead to overdoses. Also, if a user had just been through rehab and was drug free, their level of tolerance to the drug would have been diminished and would have made the user vulnerable as soon as they injected quantities they were used to while a regular user. Other famous ‘speedball’ victims include the comedian John Belushi.

When NME’s Gavin Martin interviewed Depeche Mode in September 1993, during the Devotional Tour, he found Gahan very obviously ill, his arms bruised and scratched. Martin was later told that this was as a result of the singer being bitten and scratched by fans. In interviews, Gahan denied that he had a drug dependency problem, although he once admitted that he drank too much.

Formed in Basildon, Essex, in the early-‘80s, Depeche Mode were originally lumped alongside the electro/futurist scene presided over by DJ Stevo. The band made their recording debut on his Some Bizzare compilation alongside Soft Cell and Blancmange. Depeche Mode scored their first hit with ‘New Life’, a pristine electronic pop track written by Vince Clarke, who left to form Yazoo and later Erasure.

The band established themselves primarily as a pop act in the UK, though in the US and Europe were taken more seriously. By ’87, the time of film-maker D.A. Pennebaker’s documentary 101, they were a massive stadium act, certainly as big as U2 and garnering the same critical acclaim Stateside as the likes of New Order. They also built up a fanatical, almost religious following in Europe. The music became darker, moving away from the optimistic ‘new town’ pop of their early-‘80s debut album, ‘Speak And Spell’, through to the grandiose, almost humourless ‘Songs Of Faith And Devotion’ in 1993.

Depeche Mode had been working together on new material. Martin Gore had written new songs and they were due to go back into the studio in August. At present no-one seems to know how these plans will be affected. The album is tentatively on the release schedules for the first quarter of 1997.

Whatever Gahan’s personal and drug-related problems, he now has to contend with a potentially more serious legal issue. Possession of heroin can carry a jail sentence although the amount found in the hotel room is still unknown and it is not known if the drugs belonged to Gahan. It is unlikely that a prison sentence will be handed out to someone of Gahan’s standing, though a condition of any probation will be that he attends a rehabilitation programme approved by the Los Angeles courts.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

SINGLE REVIEW

BARREL OF A GUN - released February 3, 1997

""Do you mean this horny creep" are Dave Gahan's first words back from the dead. While you'd like to forget the overdoses, turmoil and general image tarnishing that Mode endured, there's no doubt the tension helped create this master-stroke. Reclaiming their dark industrial sound from the likes of Garbage, NIN and U2, Depeche Mode release the latest in a long, long line of clever, wonderful singles. Gets better and goes deeper with every listen. Mode Rock. Single of the Week."

Cameron Adams

Beat Magazine, 5th February, 1997

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

ARTICLE

THEY JUST COULDN'T

GET ENOUGH

by Phil Sutcliffe

Q, March 1997

_____

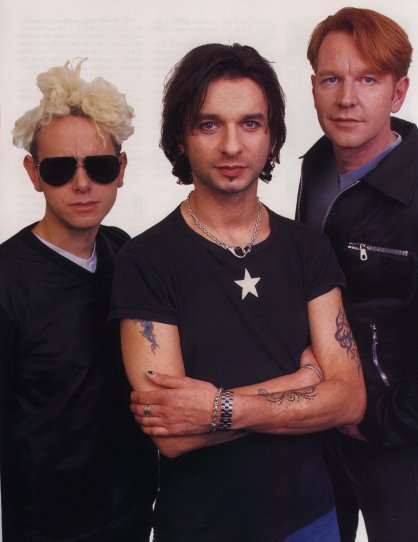

Their last tour was one of rock's great nightmares. The singer was a junkie, the songwriter was having seizures, the sturdy keyboardist had a nervous breakdown, while The Other One (and his gallstones) left the group. Now, on the eve of Ultra, the album few thought would be made, Depeche Mode tell Phil Sutcliffe they're clean, healthy and full of strictly metaphorical Vim. Photography by Andy Earl.

"I HEARD it on the radio. Dave had overdosed, nearly died, then been arrested for drugs offences. That's when I thought Depeche Mode were over," reflects songwriter Martin Gore. "We'd given him so many chances..." Recollected frustration and anger glint through the rather remote tones of his oddly Mr Bean-ish speaking voice.

Gahan's latest chance - six years into a heroin addiction which had defied two stints in rehabilitation clinics, overdoses and a suicide attempt - began last spring when he joined Depeche Mode at Electric Lady, New York, to record the vocals for Ultra, their ninth studio album. Gore had written the songs and sketched in backing tracks with producer Tim Simenon. All Gahan had to do was turn up and supply the vocals.

"But he was hiding his habit from us again - lying to us" sighs Gore, with a creak of black leather trouser on black leather sofa. "Saying things like, 'Alice In Chains are in town next week, but they won't want to hang around with me any more, now I'm clean.' We got one usable vocal out of him in four weeks and we told him, 'Go home to L.A. and sort yourself out. We'll record you later in the year.' Dave seemed quite happy to go along with it."

Gore and Andrew "Fletch" Fletcher, the band's keyboard-prodding business head and strategist, flew back to London. But, not long after, came the dread newsflash.

"Of course, I felt sympathy," Gore allows. "But I also thought, How seriously is he taking this? We're slogging away and he's so (pulls back from something harsh)...ill that he's never going to be fit to carry on."

Quite a relief, then, that just along the sofa at Abbey Road, where Ultra is reaching a civilised conclusion, sits David Gahan, sound in wind and limb. Clean - and, like every recovered addict, bare-armed to prove it - he's a proper friend once more. He listens attentively to Gore and Fletcher's criticisms and shows due concern when they describe their own crises of recent years: the cerebral seizures, the nervous breakdowns and, inevitably, gallstones, which finally prompted the collective realisation that life in Depeche Mode was killing them.

"FOR nearly 10 years we never put a foot wrong, we made practically perfect progress," opines Fletcher, now 36. Starting in 1980, the minute they traded guitars for dinky synthesizers, they commenced a brisk development. Where once they'd covered Lieutenant Pigeon's Mouldy Old Dough, they were alchemising the inspiration of Can, David Bowie and Einsturzende Neubauten into an airy, clever, semi-industrial bip-pop. They charted as relentlessly as Sir Cliff.

The potentially terminal departure of debut album songwriter Vince Clarke (to Yazoo, and later Erasure, replaced long-term by the musicianly and studio-wise Alan Wilder) only gave Gore the cue to whip out his songbook of ambivalent ruminations on relationships, religion and politics, illuminated by distinctive S&M domination and enslavement imagery (he claims to have used the word 'knees' more often than any other lyricist).

Ever whistlesome, yet dark as death at times, they made the cover of Smash Hits repeatedly while their adventures with found-sound industrial beats would influence house and techno playmakers like Todd Terry in New York and Derrick May in Detroit.

Then, in 1990, they released Violator, a career-best Number 2 in the UK and 7 in America. Worldwide sales of six million trebled those of the foregoing Music For The Masses.

"We'd been ticking along nicely, never an unbearable level of attention paid to us," Gore, 36, reminisces. "Then Violator took off and it went over the edge."

So did Dave Gahan ("Ger-haan", though he's given up trying to standardise the Irish pronunciation). Conscious that he was nearing 30, always a recreational drug user and drinker, on the World Violation tour he deliberately set about transforming himself into the rock god-cum-monster of his more garish fantasies. Introduced to Jane's Addiction circles by Teresa Conway, previously the publicist on Depeche Mode's 1988 American tour, Gahan lost touch with the shiny-faced boy of old. He acquired long hair, a goatee and loads of tattoos; ten hours of pain went into the showpiece pair of wings that illustrate his shoulder blades.

To complete the picture, he took up heroin and left his wife, childhood sweetheart Joanne, and 5-year-old son Jack. Achingly aware that he emulated his own father's desertion when he too was 5, Gahan, now 34, contrives no excuses.

"My vision got cloudier and cloudier because of what I was putting into my body."

Feeling the pressure themselves, after the tour Gore and Fletcher went home to restore their resources with 'sane domestic life'. Their first children were born. Gore withdrew to the Hertfordshire countryside with his Texan-born wife, Suzanne, and, in due course, wrote Songs Of Faith And Devotion. With his wife, Grainne, the entrepreneurial Fletch opened a restaurant, Gascoigne's, in St John's Wood.

GAHAN moved to Los Angeles and married Teresa Conway in a ceremony at the Graceland Chapel, Las Vegas, serenaded by the resident fake Elvis. Smitten with grunge, enraptured by Rage Against The Machine's metal/hip hop fusion, he thought about leaving Depeche Mode. Then Gore sent him a tape of the new songs. He loved them.

So he flew to Madrid to start recording. But when he met the band for the first time in several months, they just stood and stared at him. He remembers the moment.

"I'd changed, but I didn't really understand it until I came face to face with Al and Mart and Fletch. The looks on their faces battered me."

Deeply disorientated by Gahan's deliberate metamorphosis, for the very first time the four found that they couldn't work together. They took a break, then reconvened at the Chateau Du Pape, a residential studio in Hamburg. The shock that greeted the new Gahan had worn off. They adjusted and progressed.

"Dave would come forward on a real burst of energy, do a vocal, then disappear to his room for a couple of days. It was a bit odd," Fletcher notes with phlegmatic understatement.

Gahan thinks it was Wilder who eventually confronted him. "He used to do quite a bit of snooping around and he found some works in my room."

"Then we had our first ultimatum-meeting with Dave," continues Gore. "We said to him, You've got to sort yourself out. You're putting yourself in danger."

"They were genuinely concerned about my health," acknowledges Gahan. "Of course, I couldn't see that. I said to Mart, Fuck off! You drink fifteen pints of beer a night and take your clothes off and cause a scene. How can you be so fucking hypocritical?"

He stormed off to immerse himself in the pleasures of his addiction's honeymoon period.

But it was Fletcher, the commonsensical 'backbone' of the band, who came apart first. He had a nervous breakdown. Hospitalised for running repairs, he discharged himself too soon. The Songs Of Faith And Devotion tour, one of rock's great nightmares, was about to begin.

THEY took a therapist on the road with them. It didn't really work because, although Fletch saw him occasionally, the rest of us never did," chortles Gore. "After six weeks, we knocked it on the head."

Songs Of Faith And Devotion was an instant Number 1 in the United Kingdom and America. Consequently, the tour grew and grew.

"For us, more workload means more partyload," Fletcher attests. "I know it's a cliche, but wherever you go, everyone wants to scream at you, photograph you, take you out. For the night, you're the kings of the city."

"When you finish a concert and every door is open to you, it's very hard to say, Actually, I'm off to bed," argues Gore. "I went to bed early once in fourteen months on that tour - at Park West, outside Salt Lake City."

He lets rip a rare unbridled guffaw at the thought that he can remember such a thing amid the mayhem.

Their personal dislocation worsened. They took to separate limousines as well as separate dressing-rooms - Gahan's was a fetid black-candlelit lair, whence, after the show, minions would cart his smack-blasted body back to the required hotel.

"Remember New Orleans?" enquires Gahan, with the ambivalent merriment of a man reviewing his past as a pillock. "At the end of the gig I couldn't go back for the encore, Mart had to do a song solo while all the paramedics rushed me off to hospital. I'd overdosed, I'd had a heart attack. Next day, we didn't think any more about it.

"Then there was Mart having a full grand mal seizure in the middle of a business meeting at the Sunset Marquis hotel in Los Angeles. He keeled over, banging his head on the floor, making these weird noises."

"I really thought the whole tour was over," Fletcher recalls.

"That was the first thing that went through your mind, was it?" rails Gore, ever amused by Fletcher's pragmatic ways.

The songwriter regained consciousness within the hour to face severe finger-wagging from the hospital doctor. He'd had a fit brought on by stress, alcohol and the rest. Then, Gore realised that it had happened once before, when he was alone in a hotel room. He had also suffered panic attacks when his heart raced and he thought he was "going to die at any moment". Sensibly afraid, he took several steps back from the precipice.

Functional, if tawdry, order was briefly restored, with only Wilder's grumbling gallstones to fret about.

However, when, with four months left to go, the tour deplaned in Hawaii, Fletcher's fast-evolving depression reached such a bleak pitch that Gahan and Wilder approached Gore to demand his early departure.

"It was very difficult," muses Gore, unhappily. "Andy's been my closest friend since we were twelve. But, for the others, he'd become unbearable. I justified it by thinking that it would be better for him if he went home and got professional advice."

Fletcher, who was replaced by the band's PA Daryl Bamonte, brother of the Cure's Perry, saw his substitution as blessed relief. His misery had taken a peculiar turn.

"With the targets, the deadlines, the partying, the excess, I just lost it. I had an obsessive-compulsive disorder which made me displace this stress into worries about bodily symptoms. This sounds terrible, but I thought I had a brain tumour. I couldn't sleep. I couldn't think, this headache wouldn't go away. I had tests. It wasn't a brain tumour, it was a breakdown.

"Back home, I went into hospital for four weeks. I've recovered since. I took up yoga, relaxation. I think I'm a much stronger person now. Hopefully, there won't be a repeat."

The tour stumbled to its conclusion in July, 1994. For the final US leg, Gahan wangled a support spot for his presumed narcotic soulmates, Primal Scream. But, insiders allege, the Scream were so shaken by Depeche Mode's level of excess that, thenceforth, they fervently forswore sin, and the next Primal Scream album was recorded with zero input of powder, pill or spliff. Behold, then, Depeche Mode: the band who frightened Primal Scream into temperance.

HAVING digested the tour experience, Wilder resigned, formally stating a perhaps not unreasonable "dissatisfaction with the internal relations and working practices of the group". The others credit him with painstaking studio work, but complain that he became obsessive to the irksome point where he felt simultaneously indispensable and undervalued. Beyond even-handed analysis, they sometimes shout "Wanker!" in his general direction. (Depeche Mode did not want Q to talk to him because they felt he might be "bitter": Q tried anyway, but Wilder, who is still signed to the band's label and publisher, Mute, said he "wasn't talking to anyone yet.") If that was a difficulty resolved, off-tour Gahan hit the skids. There was a "daily habit", a disintegrated second marriage, failed detoxes and a highly publicised suicide attempt.

"I was really scared. I wouldn't wish it on anyone - to go to that depth, to push yourself to a place of such...pain."

Occasionally apprised of these horrors, Gore wrote a batch of songs which, he retrospectively infers, address the theme of "trying to work life out and life never quite working", and led on to the co-option of Tim Simenon, the repairing to Electric Lady, Gahan's final speedball, and the recovery they all believe is for real.

On pain of a two-year jail sentence for using any kind of illegal drug, Gahan submitted to random urine testing. He attended the Los Angeles Exodus Clinic (cautionarily deceased alumni, Kurt Cobain and Blind Melon's Shannon Hoon). He completed the full rehab programme. He even submitted to the vocal coaching his colleagues urged on him.

"His vocals on this record are fantastic," enthuses Fletcher. "When Dave was ill some people were asking why we couldn't get rid of him, get another singer. But Dave would never come to me and say, Gore's being a pain, let's get another songwriter. His voice and Mart's songs are Depeche Mode.

"If Dave had died last May, I wouldn't have felt guilty that I didn't do enough for him. He knew exactly what he was up to and I did as much as I could. But now, after what I've been through, if he's feeling depressed - he's waiting for news about his divorce from Teresa - he can talk to me, and I can help him. He realises that I've suffered similar pains to him. Although I know Dave's volatile and he's got a lot on his plate, I hope he's going to be an inspiration, a success story."

Considering his prognosis for the singer, Gore is positive but less gung-ho than Fletcher.

"Dave is a changed person. If he started using again we would know immediately," he claims. "I'm sure it's actually helped him to have a jail sentence hanging over his head, although it's horrible to say it. He will have to stay on a path of total abstinence, because the moment he has a drink his inhibitions come down and he's off scoring."

While backing Fletcher's plan not to play live for the next six months and possibly not at all this year, Gore says he can't shake off a malaise which began long before those difficult '90s.

"Since Black Celebration (1986), I've felt our set-up could fall apart at any time. I still feel that. Hopefully, we'll get through the next six months unscathed. But you never can tell."

In darker moments, Gahan reflects that Gore and Fletcher must feel they can no longer rely on him long term.

"I put them through a lot of worry. I'm sure they think I won't last."

NONETHELESS, he's always encouraged by the uncanny empathy between himself and Gore's songs. As usual, listening to the Ultra demos, Gahan felt that the lyrics had been tailored to fit his personality and his life - the love, the drugs, the lot - although Gore has told him many times that this is simply not so."

"Well, it's good Dave thinks the songs are hand-crafted for him," decides Gore. "It enables him to give his all performing them. I suppose the illusion comes from our similar upbringings and all the years together in the band. But I never try to write from Dave's perspective. I don't think it's possible to write truthfully from another person's point of view."

Then what is the truth behind the quiet public demeanour and the faintly silly image - the childish apple cheeks, funny hairdo, louche leathers - which deflect recognition from the strength and constancy of one of British pop's most consistent and innovative writers?

"Obviously, my working-class background has an effect on me (his father worked at Ford's, Dagenham). But politics is a fraction of what I think about. Religion comes up constantly in my songs, but always in terms of questioning. To me, it's the crux of life - what is the point to all this? If there's nothing beyond birth and death, it seems futile. I'd like to think there's a grander scheme. I do believe in some higher being, some form of spirituality, but that's as far as it goes.

"I know I have my crutches - I drink too much, still - but I think maybe that the most important thing in me is I've got a love affair with life. The other day I was trying to think of one person, I mean any person, who I dislike and I couldn't. Which is positive, but terribly naive. I'm sure there are a lot of people out there that I absolutely adore who hate me."

__________

This interview included an in-depth Q&A session with Dave Gahan about his drug addiction and subsequent recovery, 'Tears Of My Tracks. David Gahan and heroin: a love story.' The session is presented in full below.

IT'S a late Monday evening at Abbey Road. Dave Gahan pronounces himself worn out. However, the long day has meant a lot to him. He got up at 6am. His 9-year-old son, Jack, had spent the weekend with him in London, but Jack's mother, Gahan's first wife Joanne, had stipulated he must be back home in Sussex by early that morning.

Because of Gahan's heroin addiction it was the first time she had allowed him to see Jack alone for a couple of years. Since he cleaned up, there had been regular Sunday afternoon phone calls and an exploratory tripartite meeting in Sussex. Then this breakthrough.

"I couldn't sleep last night, I was so worried about not waking up in time," he declares. "Joanne was very strict about getting him back on time."

You can see her point?

"Fuck, yeah. Now I can. It used to be (whimpers) Oh no, she won't let me see Jack. But that was rubbish. I wasn't available."

He is "available" now, he asserts: facing life to the last syllable of the pain he has suffered and inflicted on those who love him. Haltingly, yet with the naked candour of a recovering addict to whom concealment has come to represent personal disgrace, he begins his story.

Why did you start taking heroin?

Million dollar question, that. Well, it's no secret that I've been drinking and using drugs for a long time. Probably since I was about (pauses, calculates)... 12 years old. Popping a couple of my mum's phenobarbitones every now and then. Hash. Amphetamines. Coke came along. Alcohol was always there, hand in hand with drugs. Then all of a sudden I discovered heroin, and I'd be lying if I said it didn't make me feel, well... like I've never felt before. I felt like I really belonged.

To what?

I've no idea. I just felt nothing was gonna hurt me, I was invincible. That was the euphoria. But the euphoria was very short lived.

You've implied you planned the transition from plain Dave of Basildon into...

A monster. Well, I did. During the Violator tour. Not overnight. There were a couple of ingredients missing: a companion in doing everything it took to be a rock'n'roll star - which turned out to be Teresa, my second wife - and...the drug. I wanted to lead that very selfish lifestyle without being judged.

Your second wife was the person who wouldn't judge you?

Yeah, because she was joining in. In fact, she introduced me... (he pauses to rephrase this, carefully not ducking the responsibility)...she didn't make me take heroin, she gave me the opportunity to try it again. I'd actually played around with it back in Basildon.

Did you inject it when you were a boy?

No. But from the moment I first injected I wanted to feel like that all the time and...you can't. After a few months I was forever chasing that high and I never found it again. I was just maintaining a very sad existence. On schedule, I'd start shaking. In the morning, then in the afternoon, then in the evening. I needed my fix.

Andrew Fletcher and Martin Gore had their crises on the Songs Of Faith And Devotion Tour. What pushed you over the edge?

After the tour ended, I spent a few months in London and that's when my habit got completely out of hand. In fact, Teresa decided that she wanted to have a baby and I said to her, Teresa, we're junkies. Let's not kid ourselves, when you're a junkie, you can't shit, piss, come...nothing. All these bodily functions go. You're in this soulless body, you're in a shell. But she didn't get it.

Weren't you living in Los Angeles most of the time?

Yeah, I was in deep shit there and I didn't know whether I was going to be able to get myself out. I was so fucking paranoid, I carried a .38 at all times. Going downtown to cop, those guys you hang out with are heavy people, they have guns sitting on the table in front of them. I was scared of everything and everyone. I'd wait until four in the morning to check the mailbox and then walk down to the gate with the gun tucked in the back of my pants. I thought they were coming to get me. Whoever "they" were.

That was when I started toying with the idea of going out on a big one. Just shoot the big speedball to heaven. Disappear. Stop. I wanted to stop being myself, I wanted to stop living in this body. My skin was crawling. I hated myself that much, what I'd done to myself and everyone around me.

When did your first wife stop you seeing your son?

Usually, when he came out to visit me I'd been able to stop fixing for a while and keep it together. But it came to a point where I was so sick I rang my mother in England and said, "Mum, Jack's due here in a couple of days and I've got terrible flu. I can't cope on my own, can you come over?" I lied. There was a lot of lying going on.

She came and I tried to do the whole thing - get up in the morning, make him his little egg, tried to be the dad. But I was kidding myself. I was cheating my son and I was cheating my mother. I knew it.

One night after I'd put Jack to bed and my mum was asleep I got my outfit together and banged up in the living room. Then I blacked out, overdosed. When I woke up I was sprawled across the bed. It was daylight and I heard voices from the kitchen. I thought, "Shit, I left all my shit out."

I got up in a panic, ran down to the living room and it was all gone. So I ran into the kitchen and mum and Jack were sitting there and I said, "What did you do with my stuff, mum?" She said, "I threw it in the rubbish outside." I ran out the door and brought in six black bags. If you can picture this insanity, I'm with my son and my mother - who, as far as I know, don't know anything about what's going on with me - and I brought in six bags, five of which were my neighbours' and emptied them out on the kitchen floor. I was on my hands and knees going through other people's garbage until I found what I needed.

Then I shut myself in the bathroom. Shortly after that, there's a knocking on the door. It bursts open and my son and my mother are there and I'm lying on the floor with wounds open and everything. I say, "It's not what it looks like, Mum, I'm sick, I have to take steroids for my voice..." All this fucking trash comes out of my mouth. Then I look up at my mum and she looks at me and I say, "Mum, I'm a junkie, I'm a heroin addict." And she says, "I know, love."

Jack took my hand and led me into his bedroom and knelt me down on the floor and said to me, "Daddy, I don't want you to be sick any more." (Gahan swallows hard, forges on) I said, "I don't wanna be sick any more either." He said, "You need to see a doctor." I said, "Yeah."

Anyway, I guess my mum must have rung Joanne. She came and picked Jack up and that was the last I saw of them for a long while. My mum stayed on for a bit to settle me down. She'd say, "We don't want you to die." And that didn't stop me. That didn't do it.

You didn't try to clean up at that point?

I did, a few weeks after that. I spent Christmas with Teresa and I tried to kick it on my own. I lay on the couch for a week like a zombie. Then, one night, I turned to Teresa and said, "I need help." So I went into rehab for the first time.

When I came out, Teresa met me. We went to get some lunch and she said, "I'm not gonna stop drinking or using drugs just because you have to. I'll do whatever I want to do." She didn't use like me, regularly. But in rehab they said that if one of us wasn't going to give up, it would be impossible for the other. At that point, I knew our relationship would have to be over if I was gonna have any chance. I'd thought we loved each other. Now I think the love was pretty one-sided.

Actually, she soon left me to get her life together, as she put it. She always used to say to me, "It's all about you, Dave - if only you could love yourself." Well, that's come full circle now, because she's suing me for a ridiculous amount of money, claiming I'm responsible for her life.

After she left I stayed clean for a little while, but I slipped back into old habits and found myself going to another rehab in August 1995.

What happened?

When you're abusing yourself to that degree there's a lot of chaos around you, people who are supposedly your friends but maybe aren't. My little world, Daveworld, was completely falling apart.

I checked into the Sunset Marquis as usual. I didn't want to live at home because it was too big and empty. When I went up to my house to get some clothes I found it had been looted - my two Harleys, the studio, tapes of a few songs I'd written, the stereo system, everything down to the cutlery.

There were metal gates which you opened with an electronic clicker and the house had a coded alarm system which they even had the fucking cheek to reset, so it must have been...an inside job. Some of my so-called friends had gone in there, knowing that I was away in rehab. I thought, I can't believe this, this is my fucking life.

How did you react?

I went back to the Sunset Marquis. I rang my mother and she said Teresa had told her that I hadn't been to any rehab, I wasn't even trying to get clean like I'd promised - and I was trying, I was doing the best I could. I quickly got loaded and drank a lot of wine, took a handful of pills. I went into the bathroom and cut my wrists. Uh, there was a friend with me.

It was a cry for help then?

Absolutely. Now I realise that. I wanted someone to fucking help me, but I didn't know how to ask. And do you know why? Because I thought I could do it on my own. The biggest pisser to me was realising that I couldn't. I'd had all the success and I wasn't prepared to admit I was powerless over fucking drugs and alcohol. And I was. And I still am. And will be every day of my life. Now, where was I?

Your suicide attempt.

Yeah. In fact I remember now, I was in the middle of that phone call to my mum and I told her to hold on, I'd be back in a minute, went to the bathroom and cut my wrists, wrapped towels round them and came back to the phone and said, "Mum, I've got to go, I love you very much." Then I sat down with my friend and acted like nothing was going on. I put my arms down by my sides and I could feel them bleeding away. She didn't have a clue what was happening until she noticed this pool of blood gathering on the floor.

When I woke up I was in a psychiatric ward, this padded room. For a minute I thought I might be in heaven, whatever heaven is. Then this psychiatrist informed me I'd committed a crime under local law by trying to take my own life. Only in fucking L.A., huh?

I was locked up in there for a while, but as soon as I got out I was up to my old tricks. I'd clean up a bit, then use again. Every time I needed more, wanted it quicker - there was never enough. I just have to keep fucking going till I black out or whatever. That's my problem. Any addict's problem. They don't know when to stop. I didn't know when to stop.

Which is why, when you went to New York last spring to record the vocals for Ultra, you could hardly sing a note?

The only vocal on the album that I recorded at Electric Lady - the only vocal I performed high - was Sister Of Night. I can hear how scared I was. I'm glad it's there to remind me. I could see the pain I was causing everybody.

What did you do after the band meeting in New York where they asked you to clean up?

I flew back to L.A., the Sunset Marquis, and promptly went on a massive binge, totally out of control. By then I was shooting a mixture of heroin and coke because neither of them were cutting it on their own. It was a particularly strong brand of heroin called Red Rum which has killed quite a number of people recently. Of course, I just thought it referred to the racehorse until someone pointed out that it spells 'murder' backwards.

There was something weird about that night, May 28, 1996. I remember saying to the guy I was with, "Don't fill the rig up. Don't put too much coke in it." I felt wrong. I woke up in hospital hearing one of the paramedics saying "I think we lost him." I sat up and said, "No you fucking haven't." I'd had the full cardiac arrest, my heart had stopped for two minutes. I'd been dead, basically.

Later, a detective read me my rights and I was arrested for possession of cocaine and needles. I was handcuffed to a trolley. Straight from hospital they threw me into the county jail for a couple of nights, in a cell with about seven other guys. A scary experience. But not enough to scare me into quitting.

As soon as I was bailed, I got what I needed, checked into the Marquis and carried on for another couple of days. Until I suddenly started thinking, "What the fuck am I doing? I died!" I went back to the house I'd rented in Santa Monica and, um, sat on the couch and realised I was going nowhere...I thought I was going to die. When I shot up, there was absolutely no feeling at all.

Then our manager, Jonathan Kessler, rang and told me there was a meeting with my lawyer about the bust. But when I showed up, it turned out it was a full intervention. A Los Angeles specialist called Bob Timmons was there. He's worked with a lot of addicts in the entertainment business.

They all said, "You're going into rehab right now," I said, "No fucking way." They said, "You are." I said, "All right, tomorrow" - thinking I could go home and cook up before I went, you know? But they said, "No, now." I was like, "What about this evening?" "No." I said, "A couple of hours. I need to call my mum." They let me go. Jonathan said he'd come and pick me up. I went home, did my last deal, had my last little party and checked into the rehab.

This time it worked?

I've been more than six months clean now, and when I say clean, that's no drink, no pills, no dope, no heroin, absolutely nothing. If God handed out drugs and alcohol I had my fair share and I'm done.

How did you make the break when all your previous efforts had failed?

With addiction, you've got to be willing to give it up.

What made you willing?

Falling flat on my face again and again. Being picked up by a couple of very close friends - one being Jonathan, who was always there for me, always the first face I saw when I woke up in hospital, another being a friend I met in my first rehab who I could ring and who would tell me what I didn't want to hear. I was a very fortunate junkie - I am - because I have a lot of people who care about me and weren't going to let me disappear into oblivion.

The whole way I felt changed. I was sick of hurting everybody around me. I didn't want to lose my son, I didn't want him to grow up wondering why his dad killed himself. All that hit harder and harder. And suddenly I got it. There was hope. I could change. I could have a choice...and now I have a choice every day. I have a choice about what I want to do, where I want to go, how I want to be.

The only thing I don't have a choice about is my feelings...they come and go, but they're really difficult to deal with when you've been using for a long time. You've blocked them out for so long and they come on like a speeding freight train.

You mean depression?

Yeah, this low-grade depression that you might sit in for weeks. But it passes, it really does.

I feel awkward inside about trying to explain all this because I feel like I'm trying to justify myself...but I guess I'm not really trying to justify being a heroin addict. I'm trying to explain, for the record. You get yourself into this mess. Nobody makes you take drugs. You can either take them or you can live.

What's fantastic now is spending a couple of days with Jack. Being there. Being really there. Last night at the hotel when I heard him kind of moaning and I went into his bedroom and climbed into bed with him and just cuddled him and he went back to sleep...six months ago I wouldn't have been able to do that. I wouldn't have wanted to. Because of the guilt and the shame I felt about myself.

GAHAN collects himself. He mutters, "Erm, that's about it, really," and laughs, rather embarrassed, at the peculiar sensation of saying all this in public. He reiterates that he's not asking for pity or respect or trust from his friends or Depeche Mode fans. Sympathy is not so much unearned as largely irrelevant to the internal quest for a sustaining sense of balance. One day at a time is his motto.

With a firm handshake, tired as he is, the singer says goodbye and trudges upstairs to lend Martin Gore some support in his continuing struggle with a pesky B-side.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photos by Andy Earl reproduced without permission.

See Appendix B for more on Dave's drug addiction and the troubles within the band on the Devotional Tour.

SINGLE REVIEW

IT'S NO GOOD - released March 31, 1997

"Cold Turkey comeback duties duly taken care of, it's back to something approaching groove - underlaid lovesick business-as-usual for la Mode. The emphasis being on the 'sick', for 'It's No Good' is another of Martin Gore's appallingly pretty odes to someone for whom the creak of his leather bodice awaits as surely as sweat accompanies rumpo. Amid the insistent electro diktat, Dave Gahan sings with disarming sweetness: "Don't say you're happy/Out there without me/I know you can't be/'Cos It's No Good". When it comes to such ultra-tech, yet trad toilet-seat drama, Depeche are untouchable, a fact the litany of unenlightening remixes by the likes of Speedy J and Andrea Parker only serve to emphasise."

Unknown reviewer

New Musical Express, 29th March, 1997

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

Melody Maker's Kirsty Baker, with Peter Andre, reviews the 'It's No Good' single.

MM: What more can I say?

Peter: They've come back from the dead, haven't they? And I think they've done it really well, too, though I don't like this as much as I liked some of their old stuff. This sounds a lot like U2. It's OK, I don't dislike it, but I preferred the last one. I don't really think it's their best material. But they're a respected group: I suppose you can't knock the fact they've started just knocking out song after song after song. They probably know that some will be liked more than others.

MM: But would you bring out a single that you didn't think was the best thing you could possibly do?

Peter: That's a good point, actually. I never though of it that way. Maybe they should have waited a couple more years and come back when they knew they had something amazing up their sleeves.

Melody Maker, 29th March,1997

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

ALBUM REVIEWS

ULTRA (LP) - released April 14, 1997

Downbeat

"In the run up to this release, Dave Gahan - never one to do things by halves - collared anyone willing to listen to "confess" his lurid tales of junk and rock god egotism. Despite Martin Gore's claims that he's never used his frontman for lyrical inspiration, Gahan's years of chemical maladjustment are reflected in Ultra's resolutely "downbeat" moods and words. In addition to this, Gore's dicky-heart scare on the band's 1993-'94 world tour, Andy Fletcher's nervous breakdown and the departure of electro-texturalist Alan Wilder mix blood with Gahan's problems to create an album of dry, dislocated, burnt-out and sometimes beautiful songwriting.

At a time when America is becoming fixated with "electronica" - everyone from Chemical Brothers to The Orb and "'90s futurists" Smashing Pumpkins - Depeche Mode's return to the fray is well-timed, although, wisely, they have opted out of touring for the moment. Furthermore, in stark contrast to the stadium-sized percussion loops and grungey power of their previous album, 1993's Songs Of Faith And Devotion, Tim Simenon's sparse production on Ultra is noticeably less immediate. Gone are the big, roguishly aggressive hooks, replaced by industrialised trip-hop beats and widescreen spaces in the sound. On first hearing many of the songs appear strangely unedited or incomplete, as if they've chucked out a set of demos on an unsuspecting public. Tricky, whose Nearly God project covered a Gahan song, is an obvious influence.

Fortunately, Dave Gahan's singing lights the noir-ish moods to reveal Gore's melodies amid the claustrophobic dirgery, in particular on the ballads The Love Thieves and Sister Of Night. Mid-tempo tracks Barrel Of A Gun and It's No Good are as hard as anything the band have written since ditching their initial teen-pop blueprint. Laughs are thin on the ground, although Gore unintentionally lapses into mirth-inducing "feline" wordsmithery on the lyrically comic, musically excellent The Bottom Line.

Although Ultra ranks alongside 1986's Black Celebration as their darkest album to date, it sounds lived-in and dirty rather than a bit pervy and self-consciously bleak." ****

Steve Malins

Q, May 1997

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

Common Synths!

"Seventeen years together, 30 million albums sold, and here comes another to crank the profit margin one notch higher. Except this time, it's not just another Depeche Mode album, because if it were it wouldn't arouse such ghoulish fascination. 'Ultra' is more than that, it's the culmination of a festering melodrama that could have resulted in death, but in the end settled for a near-fatal heart attack and some lengthy cold turkey.

This album is at least partly the product of one of the most harrowing rock 'n' roll sagas in recent memory. It's the tale of an unassuming quartet transformed into a colossal financial machine designed to bring gravitas to the masses: four cherubs from Basildon who were lauded as deities in America - only to discover they couldn't handle it.

Kinkier than U2, but not as perverse as Nine Inch Nails, Depeche Mode spent the early part of the '90s driving their juggernaut of angst across the States in an increasingly frenzied attempt to obliterate all memory of their early career. And it proved startlingly successful, because when the time came to start recording this album they had transformed beyond all recognition: they'd become farcical Sunset Strip burnouts.

Singer Dave Gahan was hauling his body around LA shooting it full of heroin, coke and water, Alan Wilder had acrimoniously quit the band, and everyone else was back in London trying to write new material. As backgrounds to writing albums go, this was one of the most traumatic. Yet the result is not a sleazy electro classic, but a near replica of past achievements. 'Ultra' is neither an 'Exile On Main Street' orgy of sprawling excess nor an introspective diary of personal tragedy - and suffers because of it.

That, however, shouldn't be any surprise. Gahan might have lived the life, but Martin Gore wrote the songs - and before Gahan went mentally AWOL, this was meant to be his most ambitious project yet. He might have been initially inspired by the no-smiles austerity of Kraftwerk and DAF, but this time around he intended to make an album that encompassed an entire century's worth of music; everything from blues and gospel right through to country.

There's not much evidence on 'Ultra', however, that such a grandiose scheme ever got off the ground. For all the crackling, ambient synths and treated guitars, this is a perversely comforting Depeche Mode record. The choice of collaborators is impeccable (Can drummer Jaki Leibezeit plays on 'The Bottom Line', Anton Corbijn did the cover and producer Tim Simenon added the contemporary hip-hop sheen), but the music remains as creepingly familiar as ever. There is no dramatic reinvention, and as such we're left with an album that's every bit as flawed as its predecessors.

If these songs are about Gahan's decline as seen through Gore's eyes, then they're written in such blank and generalised terms as to be almost worthless as insights into his condition. As usual, Gore's songs feed us a revolving roster of crying souls, burning bodies and martyred lovers - and, as usual, it's vaguely intriguing, but hardly essential listening. Indeed, the inclusion of a jazz pastiche entitled 'Jazz Thieves' tells you much about the sort of album that Gore has constructed.

Still, once you've acclimatised to the absence of documentary distress and radical innovation, there's plenty of scope to admire Gore's typically gloomy preoccupations and gleaming, hi-tech song structures. 'Barrel of a Gun''s brutal dissection of addiction, the plaintive steel guitars of 'The Bottom Line' and the scuffed beats and thudding cacophony of 'Useless' are all the result of Depeche Mode's ever-expanding awareness of their craft and their darkly sophisticated use of technology.

But it's still all too clinical, issues are skirted, poetry is attempted and we're left clutching another instalment of stadium-oriented angst, at a time when we were expecting reflective intimacy. The needle rarely comes anywhere near this record: four years away and you'd never know anything had gone wrong. This just sounds like business as usual. Against all the odds, 'Ultra' is just another Depeche Mode record.

See you at Madison Square Garden in six months, then." (6)

James Oldham

New Musical Express, 12th April, 1997

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Original review illustration by Paul McCaffrey. Reproduced without permission.

"It ain't easy being an '80s icon. When the very name of your band inspires memories of Ronald Reagan and Martha Quinn, it's almost impossible to remain relevant - unless you're not afraid to explore new terrain and take artistic risks. While U2, for instance, have done this partly by incorporating electronic effects into their music, Depeche Mode have gone the opposite route. With 1990's Violator and particularly 1993's Songs of Faith and Devotion, the prior decade's most arena-friendly techno-pop outfit began relying more on real instruments - guitars, primarily - to lend emotional urgency to its stark, computer-generated anthems.

On Depeche Mode's new album, Ultra, guitars are again prominent - moaning sensuously in the gently funky "Useless," groaning darkly in the eerily driving "Barrel of a Gun," wailing over bittersweet strings in the plaintive "Home." Songwriter Martin Gore has plenty of dark passion to document, having endured the tsoris of singer Dave Gahan's heroin-related suicide attempt, in 1995, and near overdose last year, as well as the recent departure of multi-instrumentalist Alan Wilder (a number of guest artists help compensate for Wilder's absence, including former Living Colour bassist Doug Wimbish and pedal steel guitarist B.J. Cole). Perhaps as a result, there are no snappy singles a la "People Are People" or "Enjoy the Silence" here. But moody, pulsating ballads such as "The Bottom Line" and "The Love Thieves" are ideal vehicles for Gahan's brooding baritone and for the band's ever-increasing sense of tender intuition. [Martin takes the lead vocal on "The Bottom Line" - BB]"

Elysa Gardner

Rolling Stone, 10th April, 1997

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.